Introduction

In Soil: The Erosion of Civilizations, soil scientist David Montgomery reviews the history of soil health in centers of world culture in order to examine the role that agriculture has played in the rise and fall of empires since the agricultural revolution beginning in roughly 10,000 BCE. He explores the importance of soil to the rise of modern civilizations, and the mistakes we have made in its management throughout our history as a species. The book suggests that the fall of every major civilization in the last twelve millenia was caused–directly or indirectly–by the mismanagement of soil, leading to what he calls an “erosion of civilizations.” Today, in an era when we often think of the strategic importance of oil–and increasingly of water–we still seem to treat soil like dirt. Because we don’t often see oil or massive bodies of freshwater, or any of the various precious metals that we use to power modern technology, we tend to think more often of their rarity and mystery. Soil–on the other hand–is omnipresent, look out your window right now and unless you’re in the middle of a large city, you’ll likely see at least some of it. There seems to be nothing particularly special about soil, and yet without it, we would be far worse off than if all the oil in the world suddenly dried up. In that latter case, we would need to quickly find another source of energy. The machines we use are, for the most part, not vital to our existence, but rather to modern conveniences. You can, for example, live without your car or phone. Also, these technologies could run off any number of energy sources. Fossil fuels are not intrinsic to their functioning. With soil, on the other hand, this is not the case. Without the things that soil supports–plants, above all–life as we know it would end almost immediately. Further, plants can’t simply be switched over to another operating system. The symbiotic relationships that they have with soil–its nutrients, its microbiome, its complex web of biotic and abiotic forces–are essential to their growth and development. As we noted in our earlier exploration of metabolism and the microbiome, the stuff that living beings consume isn’t just a fuel being fed into a machine, but the very being of the consumer itself. No soil, no plants; no plants, no life.

It should concern us, then, that in 2014, the UN released a paper warning that if we continue farming in the current way, we will have exhausted all the soil in arable lands on earth within 60 years. This was 10 years ago, so the clock is ticking. Rapidly. The problem is that the thin layer of topsoil in which crops can grow is eroding much more rapidly than it can be remade. Normally, it takes about 500 years to produce an inch of topsoil, and it is currently being eroded at an average rate of about 2 millimeters per year. That may not sound like a lot, but considering the production rate is 3 millimeters every 50 years, this addition is essentially negligible. At the time of the report, “about a third of the world's soil had already been degraded,” said Maria-Helena Semedo of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). "We are losing 30 soccer fields of soil every minute,” adds Volkert Engelsman, an activist with the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements, “mostly due to intensive farming.” There are three main culprits in this ‘intensive farming’. First, there is the sheer quantity of crops we are farming in arable areas. The crops we choose to farm–particularly corn and soybeans–have extraordinarily shallow roots, sapping nutrients out of the top layer of soil rather than drawing more evenly from deeper in the earth, and disallowing anything from growing roots and holding the soil together. When the plants are cycled out at the end of each growing year, there is nothing to prevent wind, rain, and other forces from blowing the top layers of the soil away, slowly eroding the usable, arable land. Although it may seem extreme to say this, the fields in which we farm are essentially deserts, insofar as outside of the plants intensively grown on them, nothing else lives. They are, from the point of view of biodiversity, no better than large, urban metropolitan areas. Without this biodiversity, there is nothing to add to the nutrients in the soil, meaning that even though they are the primary source of our food, they are, for all intents and purposes, completely barren. And as land becomes unfarmable, and populations continue to grow, we are compelled to cut down more forests to create new farm land, expanding this wasteland further every year. Second, the chemical fertilizers that we add to the soil to make up for the overdrawing of nutrients by mass farming kill the microbiome of the soil, burning worms, fungi, and other bacteria necessary for the health of the soil. These synthetic fertilizers, and the chemical pesticides and fungicides that are needed to fend off organisms that prey on the monoculture fields we rely on, are necessary to keep the crops fed and living, but kill off everything else that might otherwise live in the region, making these fields even more barren than noted above. Because there is nothing to hold the soil in place, and because our farming methods don’t allow soil to retain water, many of these chemicals seep down into the underground aquifers and run off into waterways, killing even more local flora and fauna, and often causing massive toxic algae blooms in lakes and streams. Finally, because of the overall impact of human life on the planet, climate change is causing more extreme weather events, exacerbating soil erosion in several ways. Increased flooding is occurring in areas that are less and less equipped to deal with it because of the lack of root structures, forests, and microbiomes that hold the soil together. Increased winds and storm systems blow the already fragile topsoil away at rates much higher than the baseline. This whole system creates a negative feedback loop, contributing to more rapid erosion and loss of topsoil as the whole nexus of causes intensifies. Although the UN report, and those since 2014, have apocalyptic overtones, soil crises in the United States are nothing new. Even before the country was founded, farmers, politicians, and scientists were concerned about waning soil fertility, and the problem has, in many ways, driven the history of the country ever since.

English and Dutch Agricultural Revolutions

The story of soil crises in the United States goes back to at least the sixteenth century. After Columbus’ voyage in 1492, Spain and Portugal began the process of conquering and colonizing the Americas, enslaving natives and destroying civilizations in the pursuit of gold, glory, and god. An initial influx of stolen gold, silver, and other precious metals and stones reached a high point with the conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521, but as indigenous populations were decimated by war and disease, silver mines began to produce less income by the third decade of the 16th century and Europeans began looking to other sources of wealth. Spain and Portugal began establishing sugar plantations, worked by African slaves, and by the middle of the century they had become the most profitable colonial scheme. The plantation model took advantage of vast stretches of conquered land on the continent to produce ecologically devastating monoculture crops that, through the use of slaves, created massive amounts of cheap product to sell at exorbitant prices on European markets. This would set the standard for future colonization efforts not just for the Spanish and Portuguese, but for the other European countries that began to launch their own missions of conquest by the end of the century.

All across Europe, advances in science, medicine, and a (relative) decrease in warfare led to skyrocketing populations through the 16th century, and nations began to look to colonization to both increase the flow of resources and ‘vent’ excess population. In England, this issue was exacerbated by the process of enclosures, in which common land was privatized in order for landlords to turn their holdings into more profitable enterprises such as the raising of sheep and cattle. Large numbers of expropriated peasants began to flow into urban areas, and the farming population dropped precipitously throughout the century. Landlords argued that enclosure was more profitable than the inefficient farming practices of the middle ages, and the English began to see the rise in incomes by way of privatization to be an ‘improvement’ of the land. Further, large numbers of protestant Dutch immigrants entered England in the latter part of the century to escape religious persecution by the Spanish Catholics, who ruled their homeland. The Dutch had begun developing intensive farming methods in the late medieval period to maximize output in the frequently flooded lowlands of Belgium and the Netherlands; they had developed techniques for draining fields that would otherwise be unable to be used for farming; and finally, they had developed a system of crop rotation later called the Norfolk Four-Course system, which incorporated a more diverse set of crops, as well as nitrogen fixing fallow plants like clover. In England, these techniques were employed to further ‘improve’ their countryside by increasing agricultural output and expanding arable farmland in an attempt to keep up with growing populations. Coupled with the religious fervor of the century, which revered hard work and saw the conversion of unused land into farms as a moral necessity, England became the incubator of the agricultural revolution that would begin at the start of the 17th century.

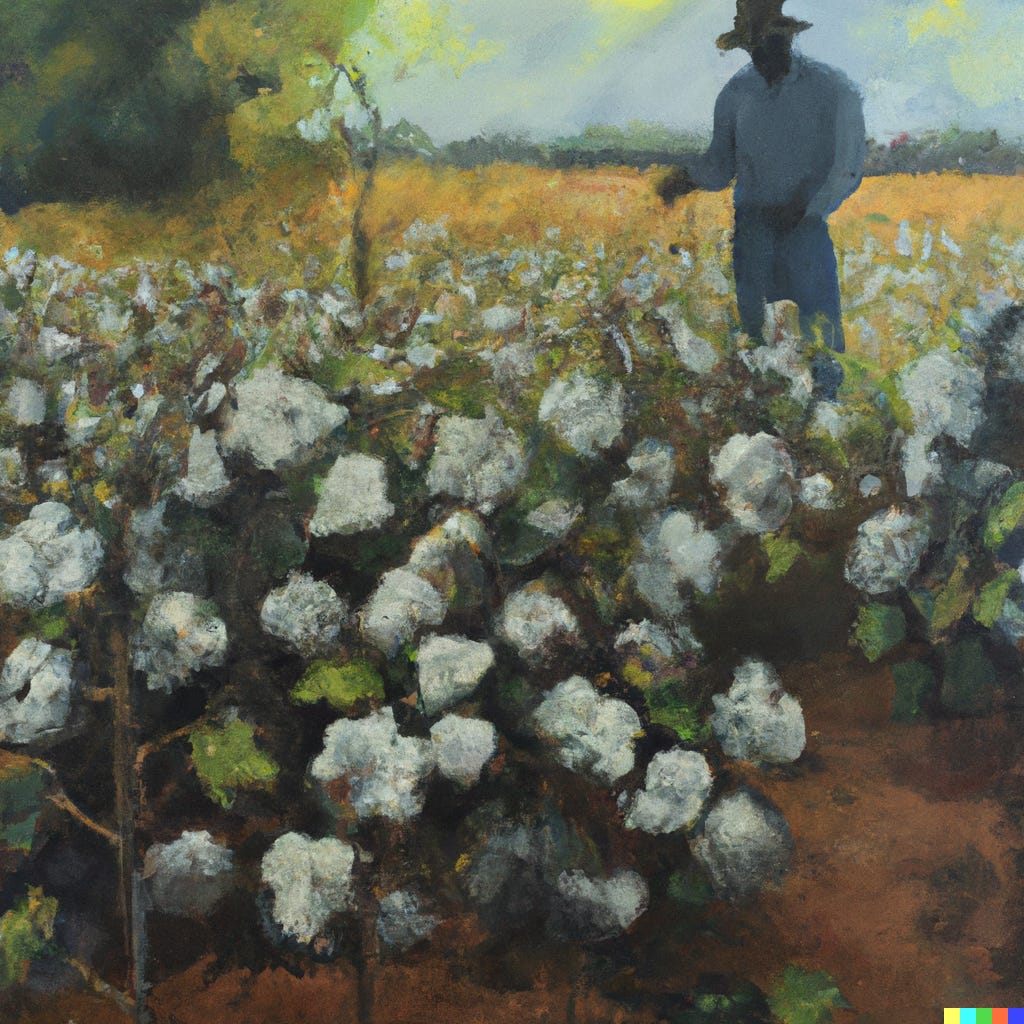

When the English and the Dutch began colonizing North America, they brought with them these intensive farming techniques and a desire to transform what they saw as wasted potential in the great stretches of the new continent. Coupled with economic pressures to produce cash crops in the colonies that came from the Spanish and Portuguese use of plantations in the Caribbean and South America, these techniques led the English and Dutch to build many of their colonial holdings around the cultivation of profitable crops such as tobacco, rice, wheat, corn, and indigo. To them, the crisis of the American soil was not that it was infertile, but that so much of it was unbelievably fertile but not yet converted to high yield, privatized, profitable production. Colonial governors of the time talked about a religious and moral imperative to put the new land to profitable use, and argued that it was their methods of ‘improving’ the land that gave them a right to it that had not been claimed by the indigenous tribes of the continent. Colonies turned their entire economies into plantation systems, so much so that for the first half of the 17th century, many colonies had to import food from England in order to avoid starvation despite being planted in some of the most fertile soils on the continent. By the end of the 17th century, tobacco production had risen to nearly 28 million pounds in Virginia alone, leading to a massive increase in slave labor, and effectively cementing the institution of the slave plantation into the economic fabric of the lower colonies. Because these plantations of tobacco, corn, and rice were so expensive, large scale growers were continuously in debt, and economic pressure made growing their holdings necessary to stay financially solvent, expanding the plantation empire by hundreds of thousands of acres before the outbreak of the revolutionary war.

Dunghill Doctrines and the Early American Agricultural Crisis

By the time the U.S. became a country, large scale plantations had completely destroyed the fertility of the soil from Virginia southward. Tobacco, wheat, and corn, the central commodity crops of the southern states, are extremely hungry and thirsty plants. Their roots are shallow and require extraordinary amounts of nutrients to grow. As Mark Sturges writes:

Planters grew the same crops on the same fields in successive years without fallow or rotation, and they did not raise enough livestock to properly manure the land and prevent soil exhaustion. Instead, as fields were depleted and yields declined, planters directed their slaves to clear new land, accelerating the problems of deforestation and erosion. This system of extensive cultivation eventually drove the planters even deeper into debt. Their farms became unprofitable, and in order to support their slaves and repay foreign debts, they were forced to bring more land into production

While the ‘crisis’ of the colonial era was a merely conceptual one, it had led to the first real soil crisis in our history. Many plantation owners of the time knew that their methods of farming were unsustainable, but also knew that if they did not continue to grow their holdings, they would be pulled under by debt in a matter of months. Even famous, large land holding politicians like Jefferson and Washington were themselves perpetually in debt and compelled to expand. These ‘founding farmers’, as Sturges calls them, attempted to put new methods of fertilizing and maintaining soil fertility into practice, leading to agricultural societies in the young nation and giving rise to what was called at the time “Dunghill Doctrines,” but the size of the plantations made it impossible to actually put these into practice at scale. Anna Tsing calls this the problem of scalability. Sure, plantations can grow easily given enough capital and slaves and produce at a profit, but this means that plantations must grow and incorporate more capital and slaves in order to produce a profit. When asked by a British agronomist why this system had taken such hold of the economies of the south, Jefferson responded that “we can buy an acre of new land cheaper than we can manure an old one.”

After the Treaty of Paris ended the revolutionary war in 1783, England granted the United States all of its colonial holdings (as if it were ever theirs to give) which extended to the Mississippi River. Prior to the war, British policy had prohibited settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, so when the new treaty lifted this limit, plantation owners began speculating on the new land in hopes of growing their holdings enough to stay in business. Jefferson’s Land Ordinances of 1784 and 85, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 were designed to make westward expansion cheap and easy by creating laws encouraging the creation of new, independent states not bound to the rule of the older, richer colonies. They were unable, however, to prevent land speculation, and the rich oligarchs of the tobacco south quickly began buying up land in the new territories. While Jefferson’s interest in creating policy that encouraged westward expansion was certainly aimed at allowing small farmers and homesteaders to create a life of their own on the frontier, it also was a lifeline to rich planters whose plantations had been steadily decreasing in output during the previous decades. In other words, these policies were crafted to resolve the problem of the first soil crisis of the United States, relieving some of the pressure that had mounted as soil fertility dropped off due to colonial plantation practices, and creating space to expand for the express purpose of alleviating ills created by destructive economic systems and farming practices.

King Cotton and the Antebellum Crisis

When Eli Whitney patented a new machine that made it possible to separate cotton seeds from the fibers of the plant, it opened a new chapter in the agricultural history of the United States. Up until that point, although the plant had been grown for profit, large scale production was not viable because of the time consuming process that preparing it for market entailed. When the cotton gin removed this obstacle, the plant began a steady march westward in the newly opened land. Jefferson’s purchase of the Louisiana Territory in 1803 added 530 million acres of land to be conquered, and cotton was the real winner of the deal. Within 10 years, the value of the U.S. cotton crop rose from $150,000 to more than $8 million. In 1800, the country was producing about 156 thousand bales of the crop, but by the start of the civil war that number had risen to around 4 million. Like the other cash crops of the early colonial period, cotton has very shallow roots, requires even more water than tobacco, and thrives in the hot, humid environment of the American South. While the south expanded westward in order to find new soil for the production of the plantation system, the north began to industrialize and became the world’s leading producer of textiles in the early part of the 19th century. The growth of northern manufacturing was able to grow at such a rapid pace, especially after the war of 1812, in large part because of the rapid expansion of cotton plantations in the south. That is, while southern agriculture was destroying the environment below the Mason-Dixon line, it was also powering the growth of increasingly toxic development above it. The two grew in tandem, so that much of the wealth of the north was created by, and in turn encouraged, the intensification of a new soil crisis in the South.

By 1848, when the Mexican-American war led to the other massive territorial expansion of the 19th century in the Mexican cession, the soils of the deep south, from Virginia to Louisiana, were largely unable to sustain any crops whatsoever, and the economy of the old south shifted gradually from the production of cash crops to that of human bodies. The importation of new slaves was outlawed by an act of Congress in 1800, and went into effect in 1808, meaning that in order to maintain the slave labor needed to keep the machine of the southern plantation economy running, the population of enslaved African Americans had to be created within the country itself. As soil fertility crashed, the model of profit making shifted from the exploitative agricultural practices of the colonial period to something like the factory farming of the 20th century in order to produce black bodies. These slaves were shipped from the deep south westward as the century wore on, supplying the new plantations of Texas and the New Mexico territory with the labor necessary to perpetuate the plantation system there after the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. After the Missouri compromise of 1821 created a system in which new states below latitude 36° 30' would allow slavery, while making it illegal above that line, a race westward began on the part of both the north and the south to gain territory in order to gain an upper hand in Congress. While the economies of the two parts of the country were deeply intertwined with one another, each still wanted to be able to set policy and legislation that would benefit their own particular interests. A new slave state would mean more seats in the Senate and House of Representatives, and vice versa. As the south expanded in order to deal with their crisis of soil fertility, the north also encouraged westward expansion in the forty years between the compromise and the start of the civil war in order to maintain political balance. Parties like the Free Soilers emerged in this period to oppose the expansion of slave territories, and eventually the Civil War brought the institution to its end in order to check the unbridled growth of the plantation system. In other words, the political history of the antebellum period was shaped in a deep way by the ongoing, rolling soil crisis that had begun in the colonial period.

The Guano Islands Act and the Post-War Crisis

In the same decade that Texas and California entered the United States, a German scientist named Justus von Liebig published Die organische Chemie in ihrer Anwendung auf Agricultur und Physiologie; or, in English, Organic Chemistry in its Application to Agriculture and Physiology. In it, he demonstrated that soil fertility was a matter of chemistry, a radical idea at the time. Before this point, farmers really only had guesses about what made some soils more capable of producing crops than others. They were vaguely aware that adding manure and certain other materials to the earth helped, and it had always been known that it was better to let fields lie fallow for at least a year, but beyond this, the process was not much more than myth and superstition. Liebig’s research showed that soil fertility came down, essentially, to the presence of a few essential elements: carbon, phosphorus, potassium, nitrogen, and some other trace minerals. Many of these elements had only been discovered in the previous decades, and were still only partially understood. Most importantly, perhaps, was the discovery of the process of nitrogen fixation by Jean-Baptiste Boussingault just a few years before Liebig’s text was published. While nitrogen makes up nearly 80% of earth’s atmosphere, plants are unable to absorb it through the air in the way they absorb oxygen. Boussingault discovered that in order for plants to actually use nitrogen, it must undergo a process whereby it is “fixed” into a solid form and made accessible to plant roots. Unlike carbon, the other important elements described by Liebig need to be added to soil in order to allow for plant growth, with nitrogen in particular acting as the main limit to the production of food in previous millenia.

One of the richest sources of usable nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium is bird and bat guano. In 1856, armed with this knowledge, the United States passed the ‘Guano Islands Act’ in order to encourage its importation as a means of combating the mid-century soil crisis caused by the expansion of cotton plantations and an exploding population. The act enables citizens of the United States to take possession in the name of the United States of unclaimed islands containing guano deposits. The islands can be located anywhere, so long as they are not occupied by citizens of another country and not within the jurisdiction of another government. Within a few years, more than 200 islands had been claimed in the Atlantic and Pacific, prompting an expansion of the U.S. Navy in order to protect business and shipping interests. Within a few decades, entire islands had been stripped of their deposits and the worldwide supply was rapidly dwindling. An entire industry and military presence had grown up around the guano trade, however, and as companies began to see the rate of profits fall, many turned to other profitable industries, such as the cultivation of tropical fruit. This led to the establishment of hundreds of overseas bases, banana republics, and imperialism in the Pacific, such as the overthrow of the kingdom of Hawaii in 1887. In addition to ongoing westward expansion in North America, by the turn of the century, the ongoing soil crisis had effectively led to an overseas empire.

World Wars and the Green Revolution

As it became clear that guano and other sources of nitrogen would be unable to solve what had by this point become a perpetual soil crisis, scientists and politicians in the United States began to look for new sources in order to maintain agricultural productivity as the world population neared 2 billion. The answer came when German scientists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed a process for converting atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3), a more stable and usable form of nitrogen, by a reaction with hydrogen (H2) using an iron metal catalyst under high temperatures and pressures. The Haber-Bosch process was purchased by chemical company BASF in 1909, and by 1910, they had created an industrial process for producing it at larger scales, but still not large enough to keep up with the agricultural needs of a world that was, once again, rapidly depleting soil fertility even as its population was continuing to grow exponentially. During the first World War, however, the German government invested in BASF’s industrial facilities in order to produce nitric acid, a precursor to the nitrates used in explosives. In order to supply the army with ordnance during the conflict, the process was perfected and scaled to absolutely massive proportions, substituting uranium for osmium as the catalyst of the reaction and thereby creating an industry for its production that would fuel the coming era of the atomic bomb. In other words, the two most deadly explosives of the twentieth century were also caused, indirectly, by American soil crises.

The war also shifted international food production to devastating effect in the United States. When Europe’s agricultural production was disrupted for the latter half of the 1910s as war raged across the continent, prices of exported grain and other food products skyrocketed. Demand did not wane in Europe, but production did, and American farmers saw massive windfall profits until production got back to pre-war levels in the middle of the 1920s. The success of farmers in this period caused banks to begin giving out an unheard of amount of loans as American families and immigrants fleeing war in Europe poured into the west to get in on the action. These loans were made at steep interest rates, but new farmers accepted them because of the continued rate of profit as cheap land continued to be available thanks to the homestead act. Then, prices plummeted in the middle of the decade when European farmers began to grow again. Many farmers went bankrupt, leading to foreclosures and financial chaos as a large portion of the country suddenly were deep in debt, prompting the panic and bank runs that began the Great Depression in 1929. Then, after rapidly converting millions of acres of previously deep rooted prairie land into shallow rooted grains like wheat and corn, and suffering a number of years of unusual drought in the early 30s, massive dust storms began to tear through the west in a period known as the dust bowl. These storms were thousands of feet high, and left houses and people buried beneath the dirt that was suddenly without any stabilizing roots. In 1935, a storm blew all the way from Oklahoma to Washington, DC, where the soil conservation act was being voted on, prompting a sudden change of heart from recalcitrant senators and becoming one of the central acts of legislation in the New Deal.

Go Big or Get Out, Soil Crises in the Late 20th Century

After the first world war, the chemical companies that had grown up during the second industrial revolution beginning in the 1870s took the large scale production facilities and processes that had fueled the war machine and turned them back toward Haber and Bosch’s initial intention, i.e. the production of synthetic nitrogen for fertilizer. The first commercially available fertilizers became available on the market in the 1920s, and became the primary source of nitrogen within a decade. At the same time, by the end of the decade, the first synthetic pesticide had been developed for use in anti-malarial applications, and became commercially available by 1940. DDT, first synthesized in 1874 by Adolf Baeyer, would become the most widely used pesticide in the coming decades until its carcinogenic and ecocidal effects were made public with the publication of Rachel Carson’s influential book Silent Spring in 1962. Together, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides would replace organic farming methods in a process known as the “Green Revolution.” A misleading name, given our intuitions about what “Green” means today, but at the time, it referred to the flourishing of plant life that these chemicals allowed.

Like the Great War of the 1910s, the second world war also had a deep impact on American agriculture in several ways. As millions of young men were drafted after 1941, the working population of the country decreased across the board. Even though Congress authorized military deferments for farm workers in 1942, agricultural employment dropped by one million between 1940 and 1945. Many soldiers who returned would not end up going back to the family farms, settling instead in the booming suburbs of growing American metropolises. While U.S. total population grew from around 90 million people in 1910 to around 150 million people by 1950, farm population declined from around 30 million people to around 25 million people in the same forty years.Farmers instead accelerated the use of mechanical equipment, a trend that would continue after the war as the industrial factories producing weapons, planes, and boats turned to the production of tractors and other farming equipment. This leap in technology allowed the acreage of commodity crops to actually increase during the war, with harvested acres of corn, wheat, and oats increasing by 9%, 15%, and 22%, respectively, and the value of US agricultural exports growing from $517 million in 1940 to nearly $3.2 billion by 1946. As the population drifted away from agricultural production and increased mechanization made farming more efficient, many small farms were consolidated into massive operations. While the average farm size was 142 acres in 1900, it had grown to around 250 by 1950. After the war, the department of agriculture under secretary Earl Butz exacerbated this trend by passing policies that encouraged the growth of farms through the use of large commodity crop subsidies, in a policy he described as “go big or get out.”

Conclusion

It is the massive size of farms, the increasing dependence on harmful pesticides and synthetic fertilizers, and an economic system that encourages the same monoculture plantation systems that dominated the early American landscape that have put us in the position of soil crisis that we find ourselves in today. All of this is not to say that we shouldn’t take this current soil crisis seriously, you shouldn’t walk away from this lecture thinking that since we’ve always been in a soil crisis that this one isn’t as big a deal as it seems. It is. We have perhaps reached a breaking point, where the trajectory we have been on since the 16th century begins to finally crack. How we decide to deal with the soil crisis of the 21st century will determine whether we continue to be able to live on this planet or not.