Introduction

Everyone has encountered them in some place or another. Sometimes they’re conceived of as lines, chains, webs, sometimes as circles or cycles. They all share the fact that they represent the movement of some key element through a complex system of nodes and connections. This movement can be conceived of as the transfer of the element through a series of points or as the metamorphosis of the element into different forms. Energy, calories, life, food, etc. They represent the interconnectedness of life as a gastronomic relation. A system in which our connection to other humans, animals, plants, and non-organic entities is mediated by nourishment. These models are the schematization or systematization of the fact that all life on earth is dependent on the consumption of some other life, on the symbiosis between beings who are mutualistically or parasitically bound to one another in every being’s process of nourishing themselves, and ultimately dependent on the elemental forces which serve as the basic inputs which become organic life. We call them food webs, food chains, nutrient cycles, and so on. They represent to us in images and symbols the most basic facts of existence on earth that we have been exploring in the first eight weeks of this course: that we are made of others, that we must constantly consume others, that our being is the result of our relationship with others, that without antecedent life forms, our form of life could not persist. That is, they are the representation of the ideas we have been discussing, this time not grounded in the internal experience we have of them through reflection on metabolism, microbiomes, taste, the interpersonal relations these imply, and so on, but a second order presentation of the significance of those experiences. The creation of a schema that is grounded in the ideas we encounter in our reflection on nourishment.

Let’s take one of the first models that we encounter as far back as elementary school: plants photosynthesize using air, light, nutrients from the soil, and water; this produces the sugars and other basic building blocks of life that are metabolized by “primary consumers,” like herbivores and omnivores in their capacity as phytovores (plant-eaters); these “primary consumers,” in turn become “secondary producers” which are eaten by “secondary consumers,” small predators which consume the bodies of the beings preceding them; “tertiary consumers” in turn consume this secondary group, which become “tertiary producers,”; and this relation iterates n amount of times until we come to the “final consumer” or sometimes “apex predator” which metabolizes other beings, but is not itself metabolized by any other consumer. That is, only the final link in the chain is not itself a producer, but only a consumer. Finally, in such a model, each step in the chain is not just a producer and/or consumer, but also perhaps more importantly, a distributor: the first links in the chain can be seen as facilitating the movement of energy from the site of its production (at first in plants), to the other links in the chain. Ultimately culminating in the delivery of energy to the final consumer, for whom this chain seems to exist. To put it in concrete terms: grass photosynthesizes and is eaten by grasshoppers, which are eaten by frogs, which are eaten by birds, which are eaten by humans. This simple model expresses the movement of life from “lower” forms of life to “higher” forms of life, a single-direction flow that culminates in the persistence of a being in which the elements of life “end,” or “tend towards.” In this model, we are often told that it is “energy” that moves from one tier of life to the other.

This elementary model conceives of life as a series of tiers moving upward, an idea that in the middle ages came to be known as the “great chain of being.” In this model, Christian theologians, drawing on the work of Plato and neo-Platonists like Plotinus, organized life into a kind of ladder which proceeds linearly from one being upward. At the top of the ladder is the “highest” form of being conceivable: God. Below God, there exist the various orders of the angels and other spiritual beings that don’t have physical form. Underneath these hierarchies, exists humanity, the highest form that was attached to a material body. From here, other orders of animals “descend” to the most basic forms of life known at that point: worms, snails, snakes, and so on. The movement of this ladder downwards represented a decrease in the perfection of a thing’s form, with each successive rung signifying a lower degree of participation in being. At the bottom of this ladder, then, was the being farthest from God, the one that partakes the least in His perfection, the antithesis of God’s being. Depending on who you ask in the middle ages, this could either be pure, soul-less matter, or some malevolent being such as the devil. The Christian theologians of the middle ages saw each subordinate rung of the ladder to be dependent on the ones above them. That is, the purpose of the beings lower on the rungs was to provide for those above them. In other words, lower beings exist for the sake of the higher ones, they are there to support those forms which partake in a higher degree of perfection. On this reading, matter exists for the sake of plants, which exist for the sake of animals, which exist for the sake of humans, which finally exist for the sake of God. Life, in this conception, is a constant motion upward, towards the heavens, where the corruption of the body is no longer a factor.

Our elementary food chain shares a number of attributes with this model of the world. The “earlier” points in the chain are moments on the way towards the “later” forms, stops that energy take on their way towards the apex predator, or final consumer. They are producers which create the funds of energy which will power those beings further down the line that are said to do more complex activities. When such a model of life places humans at the end, it is because they conceive of humans as the kind of beings that can take that energy and perform more important activities that transmute the flow into more ideal forms. Animals eat, it is argued, in order to be fed, we eat so that we can perform higher functions such as the creation of political systems, engaging in sociality, producing art, generating value, and so on. In this conception, we are rightfully at the “end” of this system because we have the capacity to create forms that are longer lasting than simple bodies because we have an intellect to create with. For such a conception, the energy we receive from primary producers becomes mental, intellectual, spiritual energy in new forms, those that are more enduring because they are ideal. This medieval holdover of a worldview places humanity at the end, which is to say the center, of all models of life at a degree far removed from the environment that produces it. As tertiary consumers, we conceive of ourselves three steps away from the water, air, light, and soil that produces us, that tends towards us.

The Economy of Nature

This model, of course, is too simplistic, and leads to a number of important questions: what happens to the “final consumer” when it dies? Is it really just one thing that eats the beings that “precede” it? Do all beings really fit so neatly into a specific tier according to the nature of the kind of things they eat? What do we mean when we say that it is “energy” that moves through this line? What are the qualities and ways of quantifying this “energy”? What are we implying when we say that one group is “higher” than another? More complex models begin to tie up some of these loose ends: the being that we called an “final consumer” might not be hunted the way that it hunts other beings, but there are certainly things that eat it: parasites, carrion feeders, fungus, microorganisms. Everything that lives, dies, and everything that dies is eaten, such that there really is no “end” to the movement that we described above. As we’ve seen throughout this semester, when we begin to seriously think about food, we see that we are much more intimately tied to these elements, and a wide range of other living beings, than this linear system could possibly represent. The most basic “fix” to the linear model, then, is to bend it around, and attach the end to the beginning to create a cycle, circle, or loop. That is, you can attach the “final consumer” to the “primary producer,” by acknowledging that saprophytic fungi and other decomposers are nourished on the death of “higher consumers”, making of them a kind of producer as well. We can add more complexity by noting that many beings consume multiple types of others: tertiary consumers most often need both plants and animals to get their requisite nourishment. Not only that, but as we saw in our week on metabolism and the microbiome, when one “individual” is nourished, a whole host of beings are involved in that nourishment. We would not be able to metabolize without gut bacteria, archaea, fungi, and other microorganisms. Who exists for the sake of who here? The microbiome is certainly necessary for our life, but they also have their own agendas, their own drives for life, such that it might be easily said that we exist for the sake of them, creating an environment in which they can flourish, facilitating the conditions necessary for a whole system of beings within us to manufacture and acquire the elements they need for life. That is, just even our body, with its interconnected series of digestive and arterial systems, is both producer, consumer, and distributor. As we add more and more complexity to this model, we begin to see that the distinction between these three concepts dissolve. Or at least to become much more complicated than originally believed.

It wasn’t until the 19th and 20th centuries that these models began to take form in the shape we have them today. The discipline that formalized them was an emergent niche of the biological sciences that came to be known as ecology. This term wasn’t used for the first time until 1866, when it was described as the “science of the relations of living organisms to the external world, their habitat, customs, energies, parasites, etc.” The word is derived from the Greek oikos (a word which we encountered as early as week 1, meaning ‘home’) and logos (a word meaning ‘study’ or ‘discourse’), meaning that it was a study of how things dwell. Prior to 1866, the closest term that described this emerging approach to modeling the world was “the economy of nature,” a phrase that can be traced intermittently back to antiquity, but which really gained an intellectual foothold in the west in the 18th century beginning with the work of parson-naturalist Gilbert White. Oikonomia in the ancient world, and as recently as the renaissance, typically meant the management of household resources: how food and other necessities were produced, acquired, distributed, and consumed within the oikos. For White, nature was itself an oikonomia on a grand scale. His model of the economy of nature was one in which God was the head of the household, determining who will produce what for whom, and placing everything in nature in its right place so as to provide for the needs of everything else. “Nature is a great economist,” he wrote in 1789, for “she converts the recreation of one animal to the support of another!” In this model, beings produce, distribute, acquire, and consume through an intricate and interrelated system of relations moving in many directions, not just upwards. White’s work brings together the medieval Christian “great chain of being” and the emergent economic language of the time to create a new method for approaching the relations of support and purpose in living systems.

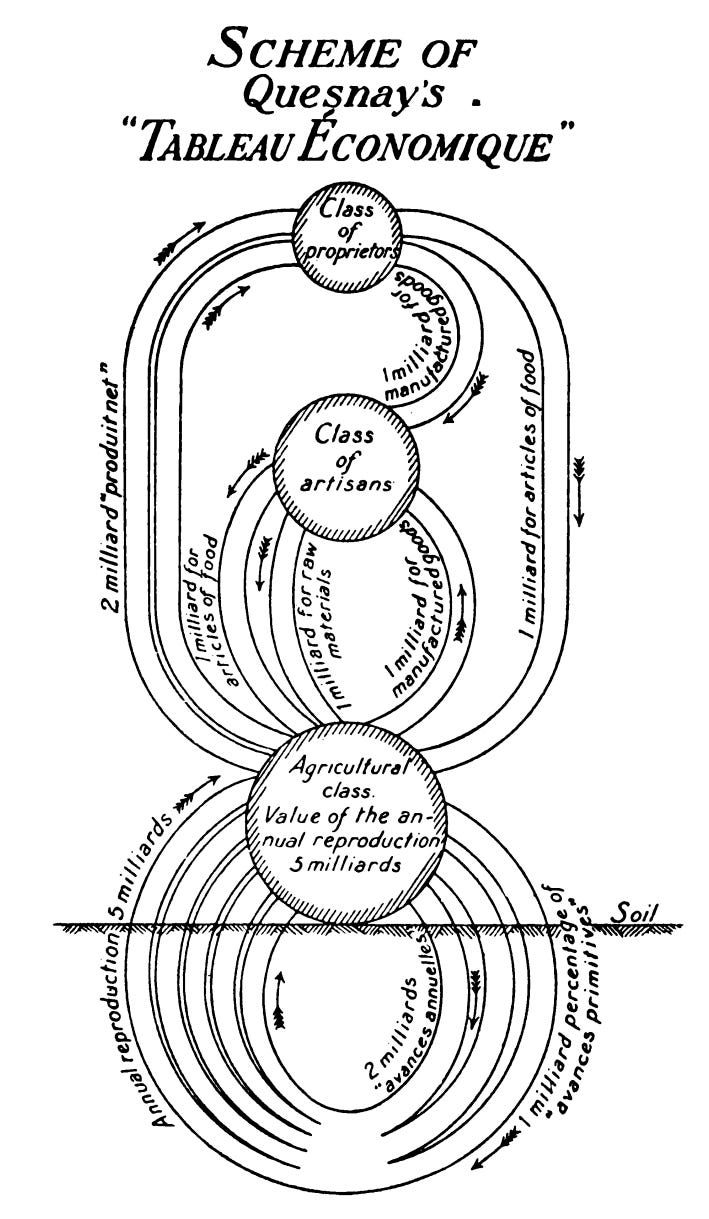

18th century economics was one that saw the emergence of the idea of an independent market idea that pushed back against the colonial-mercantilist theories of the previous centuries. Since the medieval period, what we typically refer to as ‘economics’ was identified closely with politics and military strategy. The ‘mercantilists’, whose work dominated ‘economic’ thinking between the renaissance and the early enlightenment, argued that the production and distribution of resources is a subsidiary to the governance of a nation, and thus that colonies were important in order to exert power over producers for the sake of the colonizer. Beginning with the physiocrats, who we first met way back in week 1, who referred to themselves as “Les Economistes,” economics as an independent discipline began to emerge, in which a system called “the market”, not the state, was responsible for managing the production, distribution, and consumption of resources within an area. The “school” was started by Francois Quesnay, a physician in the court of Louis XV. As a doctor, Quesnay understood the body of a state on the model of a circulatory system, in which resources had to be acquired and moved through the system in order for the system as a whole to work. He and other physiocrates such as Turgot and de Mirabeau argued that at the base of this system was agricultural labor, and with it, ultimately, land. The earth, and the products generated through the cultivation of the land, produced all of the wealth and value that circulated through the system. Agricultural labor, like plant life in our example above, is the only real ‘producer,’ while every other link in the chain is primarily a consumer. Crucial to their conception is the idea that this is a function of labor, not of government. Inspired by the idea of wu-wei, a concept Quesnay found in Chinese, and specifically Daoist, political theory, the physiocrats argued that the circulatory system–the economy–was what created the conditions for political systems, not the other way around. Against the mercantilists, for whom agricultural labor was simply a part of the operating of political power, the physiocrats took the–at then–radical position that the nobility and church were secondary to, and only acting in support of, the production, distribution, and consumption of agricultural goods, primarily food.

Adam Smith, taking up the ideas of the physiocrats, envisioned a model in which a wide range of labor produced value to accomodate and account for an emerging sector of factory production in the last decades of the 18th century. Smith argued that this ‘economy’ which acted as the circulatory system of a society was not just powered by agricultural labor, but by labor producing all sorts of commodities. What was fundamentally important, for Smith, was that human labor was mixed with commodities. It was this that created the value which powered the system. Or, to put it another way, rather than centering the “stuff” circulating through the system on agricultural products, he shifted the focus to “labor” that circulates, turning every node in the system into a producer. One effect that this shift had, which affected the next several generations of ‘economists’, was that the economy was nearly fully separated from the earth itself, not just the state. Economics in this vein, which still dominates the discourse in the present day, sees nature as an externality, an other, which it depends on but does not account for. The further development of this model of economics in the 19th century created systems increasingly separated–in theory, not in practice–from the metabolism of natural processes, deepening ecological crises.

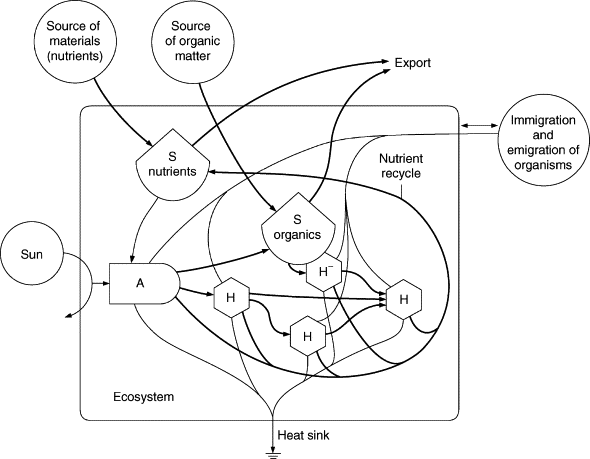

During this period, the study of nature, following the work of Gilbert White, also developed on its own trajectory. That is, through the 19th century, we see the emergence of the importance of ‘wilderness,’ or of nature untouched and unchanged by humanity, culminating in the thought of individuals like Henry Thoreau. This wilderness idea, like the independent market idea of the economists, tended to separate “Nature” off from artifical human culture, reinforcing the sharp schism between the study of nature and the study of economics. By the early 20th century, ‘ecology’ was mostly concerned with environmental systems in isolation from the human element, entirely concerned, like most sciences with attempting to describe ‘nature itself’. It is from this period that we begin to see food webs articulated in a systematic manner, as scientists attempted to articulate ecological principles in purely physical and mathematical terms. A.G. Tansley’s conception of an ‘ecosystem’ was perhaps the paradigm of this model of food webs. For Tansley, “energy” quantifiable in terms of kiloCalories, could be traced through systems in order to explain where energy was produced, where it was distributed, and how it was consumed. Crucially, for Tansley, this was not to be understood as “metabolism,” since that implied the belief in the ecosystem as an ‘organism,’ which smacked of anthropocentrism in his mind. If we are to understand nature, on this model, we can only consider humanity as a single node in the production and distribution systems of energy.

Smith’s system, like much conventional economics that follows him, assumes that each node in the network is acting according to rational self-interest. That is, they they calculate their production and consumption in order to maximize profit and minimize cost. What this means is that while the economists are concerned with production, distribution, and consumption, these are understood as rational calculation, not hunger, desire. The system as a whole is a tool for calculating the ‘best’ way of producing and distributing according to more or less mathematical equations, and the overall wellbeing of the economic system is determined not by the individual moral decisions of the individuals involved in the system, but rather by the functioning of the whole. His argument, in other words, is that the most moral system is one in which ethical considerations are inconsequential, and taking other people and places into consideration in our decisions, their hopes, dreams, desires, pains, etc. only disturbs the system as a whole. On the other hand, what Tansley, and many ecologists in his wake, forget is that all of the points in this system are not just stops on the circuit of an impersonal ‘energy’ as it moves through a network, like an electric charge moving through wire. Rather, each node is at once a producer, distributor, and consumer. By attempting to distance ecology from ‘organismic thinking,’ Tansley and other physical scientists in the ecological tradition have eliminated the fact that we are in fact talking about living beings, organisms, each with their own desire for life, capacities to labor, plans for acquiring goods, needs and wants. While economic theory might have tried to reduce the circuits of production and consumption to a calculation of interest, ecological theory removes interest altogether, as well as the productive and consumptive aspect of the system, eliminating ethical considerations from the science from another direction.

Metabolic Rift

What this resulted in, strangely, is that while economics and ecology each drifted apart according to their own particular interest, worldview, and distinct way of specializing through the 19th and 20th centuries, they arrived at a remarkably similar manner of understanding systems of production and distribution. Like two sides of the same coin. Both wanted to take an impersonal look at the scientific functioning of the movement of some important element (value and energy, respectively) through systems of production and distribution. These were to be quantifiable, and independent of external factors (its just that the “external factors” of each one were at the core of the other one: market and nature, respectively). Each discipline saw in the movement of these systems of production and distribution similar motivations: for the economists, it was our supposed drive to pursue our own self-interest through the market which could put us into conflict with one another; for the ecologists, it was the Darwinian idea that individual organisms pursue their own self-interests through resource acquisition that brought them into conflict with one another. This resulted in a situation in which each discipline had a kind of blind spot at the center of its vision, in which economists couldn’t see anything but humans circulating money, capital, and commodities, and ecologists couldn’t see anything but energy, food, or life circulating. In each case the idea was that this market, or ecosystem, selected for the ‘survival of the fittest,’ in a realm that was ‘red in tooth and nail.’ In many ways, the same underlying system was the same, but the terms of the model were diametrically opposed. As environmental historian Donald Worster put it, “scientists…were concluding that energy, more accurately than “food,” is the medium of exchange in nature, like money in the human economy.” So close, and yet so remarkably far from one another.

Marx called this phenomenon the “metabolic rift.” In this rift, the human economy is separated from the natural economy. In both economics and ecology, according to Marx, there is an inability to account for the other, an incapacity to see the economy in ecological terms, and ecology in economic terms. For Marx, following the work of the physiocrats, economic activity ought to be understood as a circulatory system which is grounded in our interchange with natural processes, but one that only did so through our economic activity. Labor, according to this model, was the capacity that we had for working with the matter furnished by nature, and the use of matter (food first and foremost, but all the raw materials of nature) for our purposes. This labor comes up, at several points in his analysis, against natural limits such as the agricultural cycle of the year, the exhaustion of human bodies, the need for sustenance, the role of natural processes like curing, growing, and setting that increased productivity cannot overcome. Conventional economics, then, misses the fundamental role that nature plays in the provisioning process, and conventional ecology misses the fact that nature is shaped by our labor, sometimes at a fundamental level. Both economy and ecology tend to see the world in terms of, on one hand, “Capital,” and on the other hand, “Nature,” but is not inclined to talk about how each exists in and through the other. World systems theorist Jason Moore suggests that we talk about capital-in-nature, or the role that labor and markets have to mold the material world around it, or nature-in-capital, the role that the physical limits of the natural world have to mold the possibilities of labor.

The ‘rift’ described above, in which “economics” drifts in one direction and “ecology” in another so that they become–at least superficially–disconnected from one another, has made it difficult to model production and distribution as an integrated system of natural processes, economic processes, political processes, and so on. In recent decades, environmental and ecological economists have begun thinking of ways to incorporate nature into economic decisions. The concept of “natural capital,” for example, or “ecosystem services” attempt to take the language of Tansley’s calculating ecosystem physics and use it to quantify nature within economic logic. Such an approach simply recognizes the similarities between these two discourses and bridges the gap between them. Whether such an approach will help mediate the so-called “rift,” or whether it will take a different approach, one that takes the approach suggested by Marx and Moore, or otherwise, is unclear. We are either way running up against the limits of nature as climate collapse accelerates, so our models for how production, distribution, and consumption will need to address this if anything is to be done.

…but Food

Ok, so what does all of this have to do with food ethics? So far in this course we have been working primarily with what we might call ‘subjective concepts.’ We have approached issues of our interrelatedness with others by questioning assumptions we have about what we are, what we mean when we talk about food, the freedom we have to choose it, the taste and texts that guide us when we encounter nourishment, and so on. At each step of the way, we have mentioned that a lot of these questions (what food is, what we should eat, what makes food good, how do we know food, etc) cannot really be fully answered until we settle some ethical questions first. At the same time, we’ve noted that in order to be a little more clear headed about the stakes of the ethical decisions we have to make often around food, it might be important to at least try to unlearn a few of our assumptions about the nature of food, of ourselves, etc. by thinking about what these ideas entail given the nature of nourishment. That is, the hope is that we’ve cleared some grounds for thinking differently about the ethical decisions that we do have to make every day.

In the next few weeks, as we begin to enter some applied ethical questions such as the issue of GMOs, the eating of animals, the moral demands of hunger, and so on, we will begin to encounter issues of production, distribution, and consumption. The subjective aspects of our understanding of food will be reinscribed into something more objective. We will be talking about them more directly as material processes where food, other living beings, etc are being produced; where we have to transport food and living beings from one place to another, pass them through markets, distribute them to where they are needed; and finally where eaters consume these goods, or don’t, and deal with the waste. At the end of the previous week, on food ethics, I suggested that all questions of ethics come down to these few areas: where should we get our food? How should we get or prepare it? And how and what should we eat? Oh, and what do we do with the waste? The concrete questions of ethics, the everyday questions that we ask ourselves when we decide what to eat, place all of our subjective intuitions into economic and ecological contexts. This means that our received notions about what economics and ecology do, what language they use, what assumptions they make, are just as important to reflect on as we enter food ethics and politics directly.

We’ve been talking about models throughout this lecture. The ways that economics and ecology have modeled the productive, distributive, and consumptive relations of deeply intertwined beings and systems. They represent attempts, from different angles, to render a model of the sites at which we encounter other living things. Ethics, as Levinas argues, is simply that: the encounter with the other. The question of what we ought to do when we encounter another, something that has moral standing, or that we recognize as having moral standing. Economics, until the 19th century, was by and large just a branch of ethics. Adam Smith, the “invisible hand of the market” guy, was first and foremost a professor of moral philosohy at Edinburgh University. Even in the 19th century, the author of the most influential economics text of the middle century, John Stuart Mill, was more well known as the author of Utilitarianism. It was conceived this way because economics was, until the market fully separated itself in theory from government and society, understood to be the study of our encounter with others, a question of the just distribution of goods, the moral value of work and consumption. Not that any of these thinkers had anything particularly radical to say about this, their moral systems generally fit the spirit of the times. They just point us to the fact that our ethical choices take place in economic and ecological contexts. These models help us contextualize the stakes and other conditions under which we make ethical choices. These ethical choices, again, in turn shape our beliefs about what food is, what our role in the world is, how things taste, and so on.

Food ethics always occur within systems of production and distribution. Really, all ethical questions likely happen within sytems of production and distribution. But it is only in food ethics that we can really see that this is the case. Food ethics, I would like to argue, reinvest problems of production, circulation, distribution, and consumption with the moral valence that contemporary economics and ecology have jettisoned in favor of scientific neutrality and objectivity. The questions of what to eat, how to eat it, who to feed, and so on, all give concrete and material weight to the otherwise abstract issues that occur in discussions of economy. Bringing the disciplines together: food studies, economics, and ecology, might go far in the direction of mending the ‘metabolic rift’ outlined by Marx. The historical systems that we outlined above treat production and distribution in increasingly abstract ways, forgetting the ethical ground of questions of resource management and substituting it with calculations. In the coming weeks, we will look at ways in which food is produced, distributed, and consumed with these ethical questions in mind once again, bringing the subjective concepts encountered in the previous weeks to invest issues of resources with the moral ambiguity which used to accompany them.