Introduction - Recap

One of the very first questions that we considered in this series was what to make of ourselves as beings that are constituted by others. Reflecting on both metabolism and the microbiome allowed us to see that our bodies are constantly making the world around us into the thing that we call a ‘self,’ and that even this ‘self’ is something that is primarily, at least by number of cells, more non-human than human. We are, in other words, beings of otherness, through and through. At that point, we considered this simply as a fact: we are made of others, and there’s no way around that. We are heterotrophs, and if we wish to continue our own existences, then it is necessary that we consume the bodies of other living things. In the chapter on food ethics in Kaplan’s Food Philosophy, the author even made an argument that we have a duty to feed ourselves in order to continue our lives. This argument was based on the Kantian claim that human beings, by definition, deserve respect and dignity, and that to neglect the basic needs of humans (specifically ourselves) is tantamount to disobeying categorical moral imperatives. Regardless of whether this is a sound argument or not, for the moment, we will take it for granted that it is good to continue our lives if we want to live, and that to want to live is a perfectly acceptable moral position. And if this is the case, then there cannot be anything inherently wrong with eating other living things. At least some of them.

In the intervening weeks, we have begun to ask more serious questions about the way that we use the world around us to build our own bodies. To have a better sense of what it is that we should eat, we first asked about how it is that we have knowledge about food in the first place. That is, after asking metaphysical and ontological questions about what food is and what we are as gastronomic beings, we began to ask epistemological questions. Questions about how it is that we make claims about food, how we understand claims about food, and how we come to have beliefs about food. We looked at various modes of knowing food, including narratives we tell about it, recipes and other texts which convey information about it, epistemological frameworks in which we verify claims made about it, and the sense of taste, which acts as our immediate, bodily relationship to it, as well as the intellectual power of judgment about it that we call Taste (with a big T). All of these presented us with information about food, as well as increasing levels of evaluatory tools. That is, increasing levels of analyzing food from the point of view of value. The first level of value that we investigated was aesthetic value, which grew out of the analysis of the modes of access that we have to food through taste. In the last few weeks, we have begun to discuss another kind of value in food: ethical value. Two sessions ago, we spent time with a number of ethical systems: virtue ethics, consequentialism, and deontological ethics. Last week, we began to build a context for making ethical decisions by placing ethical questions in food within the political and economic models like food webs and other systems of production, distribution, and consumption. This week, we will begin to ask more concretely: what should we eat? Specifically, we will consider the ethics of eating other living beings. That is, we will return to the claim that we took for granted at the beginning of the course, namely, that eating others is justified because we are heterotrophs, and that to live means to turn the bodies of others into nourishment for our own.

This week, we have three arguments for various approaches to the question of what kind of things we should eat. While the arguments for omnivorism, vegetarianism, and veganism are, I believe, relatively straightforward now that we have developed some terminology to understand the arguments, the argument of the last article is… a bit stranger. Because of this, I will spend more time working through the argument of that text. What the author wants to argue is that while we must certainly take the lives of animals into consideration when choosing what we ought to eat, there is also a case to be made for considering plants in our moral decisions about what to eat. This position does not, as we will see, claim that it is wrong to eat plants. It is, after all, impossible to get around it if we want to stay alive! Rather, what it does is make the case that our dietary choices are an open question. That is, that if we take the arguments about the reality of the lives of other beings, even those made by vegans, then we ought to continue to ask ourselves about the ethical status of all living things. It suggests that the question of what we should eat, from a moral point of view, is one that cannot be definitively answered. It is one that we must address again and again, every time we go to the grocery store, each time we sit down at a restaurant.

The Vegan Argument

In the last several decades, research into the lives of plants have begun to change the terms of the debate over the ethics of eating. Vegans and their philosophical predecessors have long argued that there is good reason for leaving the bodies of animals off of our dinner plates, but new research in biology, as well as in philosophy, is putting the logic (if not the conclusions) of these approaches into question. Most people are introduced to the theory of veganism by the activism of groups like PETA, who trace their theoretical position to the work of Australian philosopher Peter Singer. In Singer’s landmark 1975 text Animal Liberation, he makes a case against the use of animal bodies for our nourishment and enjoyment by arguing that there is, ultimately, no qualitative difference between human and non-human animal life when it comes to questions of suffering. To make his case, he refers to a concept coined in 1970 by Richard Ryder: that of speciesism. Speciesism, Ryder and Singer argue, consists in “a prejudice or attitude of bias in favour of the interests of members of one's own species and against those of members of other species.” The vegan will argue that what is essential in the question of whether it is just to subject another living thing to death or use for some other human want is not whether they belong to a particular species, but whether they have a capacity for suffering which we can ourselves understand through sympathy. If we asked, for example, whether it would be just to subject a human to the conditions of a factory farm, we would say no. We feel that the suffering of the other is real because we recognize in them a capacity for physical, emotional, and spiritual suffering which should elicit at least the abstract understanding that what we have before us is wrong, is unjust. The vegan argues that if we ask the same question about the suffering of a cow, we have no good reason to come to a different conclusion, because animals also have a capacity to express, experience, and – more generally – be subject to suffering.

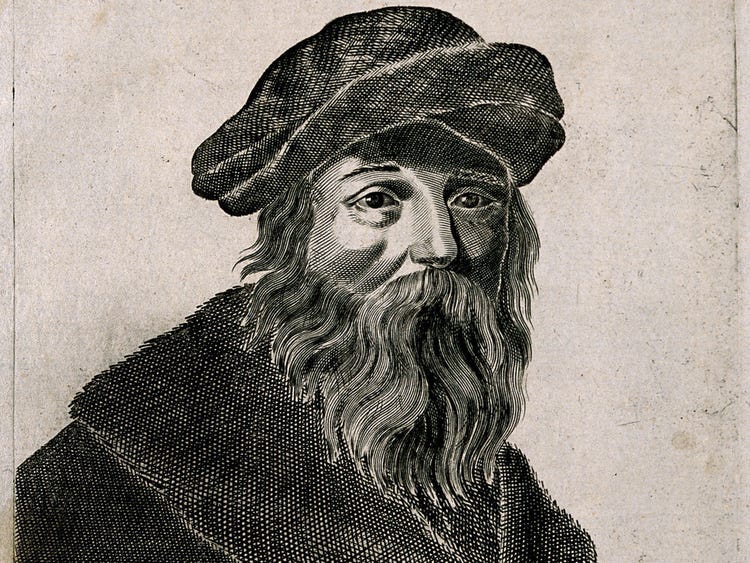

The emphasis on the recognition of the capacity of the other to suffer in Singer’s thought is attributable to the influence of the Utilitarian ethics of Victorian era England, most clearly expressed in the work of Jeremy Bentham and John Mill. For Mill, an action is judged according to its tendency to produce pleasure and remove pain for all parties involved. Although he acknowledged the qualitative difference between the cultivated pleasures afforded by human judgment – our supposed ability to experience a higher mode of aesthetic and intellectual pleasure than other animals in the arts – Mill still argued that there was no amount of enjoyment we could get out of eating even a very well cooked steak that would outweigh the death sentence – with its accompanying pain, fear of death, grief at being separated from family, etc. – that such a meal required another sensitive being to be subject to. This line of thinking seems to be a riff on a very old argument in the moral philosophy of the West which ultimately comes from Pythagoras, and is itself a permutation of mythological and theological ideas circulating the Mediterranean and east of it before the Greeks. Pythagoras was said to have stopped eating animals when he thought he recognized the voice of a deceased friend in the yelping of a dog being beaten in the agora. For the Pythagoreans, this was conceivable because of a committed belief in metempsychosis, the reincarnation of souls between animal and human forms.

Like Bentham and Singer, the Pythagoreans find in the figure of the animal a similar enough container, or form, of life-in-general to the human that by some logical operation we can create an analogy of suffering between the other and ourselves. If we follow the thread of all these tributaries of thought which contribute to the theory of veganism that has framed most of the conversations around the ethics of eating in the last few decades, in other words, it appears that the entire logic of veganism, as it emerges from the Western moral tradition, is concerned with the reduction of suffering, a logic which fits well with the culture of veganism with which I grew up, with its emphasis on showing – largely through the new media of internet 2.0 – the suffering of animals in expository undercover videos, public demonstrations involving fake blood, and so on. For this strain of veganism, the removal of things from our plates is equivalent to a reduction of identifiable suffering in the world around us.

Veganism and Zoocentrism

But notice that for the Pythagoreans, the Utilitarians, and those following Singer (modern vegans), this all hinges, as I said a moment ago, on a similarity of experience, and an expanding sense of the scope of moral consideration. In each case, we begin by fixing our moral gaze on beings that are most like us (other humans that look and live like us), push past accidental attributes to beings which are not just accidentally like us (i.e. get over racism, sexism, classism, etc. and begin to consider the moral value of any human being whatsoever), and finally consider other forms of life which share a capacity to suffer (animals with a central nervous system, and “perhaps even insects” as Singer suggests). That is, these streams of thought successively include other forms of life according to their similarity to our own being. In other words, they are, despite their best intentions, essentially anthropocentric, or perhaps more generously, zoocentric, in that they base the criteria for moral consideration on a similarity to an essentially human experience. Because we have to eat something, the veganism that emerged in the late 20th and early 21st century continued to place a fairly firm – except in the case of the neverending debate over honey – line between that which is acceptable food (plant and fungal forms-of-life) and that which isn’t (animal forms-of-life).

But plants, unlike animals, are radically different forms of life from human beings. Any moral claim that they could make upon us would be fundamentally different from the claims made upon us by an animal, which has a voice to express suffering, has eyes into which to gaze, has a face. Plants do not, in other words, suffer in a manner analogous to our own, and any comparison between our suffering and that of plants borders on absurdity. To even call the experience of plants ‘suffering’ is, as vegans will point out, misleading, if our understanding of suffering remains grounded in our own experience of what that term signifies. To consider the ethics of eating plants, in fact, seriously breaks the logic of food ethics as it is typically framed by veganism. It will not suffice to continue expanding the scope of moral consideration further and further for two reasons. First, the radical difference between plants and ourselves makes it impossible to make the comparison between our suffering and whatever it is they undergo. Second, whereas when we expand this consideration to animals, veganism institutes a ban on consumption, the same cannot apply if we were to expand consideration to plants because it nevertheless remains the case that we need to eat something if we want to maintain our own existence. What this means, I think, is that the Otherness of plants requires us to consider the ethics of eating without resorting to subtraction, to simply removing things from the dinner table on the ground of abolishing suffering. If to be alive means above all that you at once need to be nourished and that your body is potential nourishment for some other earthling, then to be alive on Earth means to end the life of another living thing, and the end of our life means the continuation of life for another living thing. Our life is the death of others, in other words, and our death is the life of others.

Veganism, and all of the traditions on which it depends (utilitarianism, Pythagoreanism, etc.) ground their position on a position which asks us to choose what kind of suffering is just and which is not, and on this ground maintain the dividing line between animal and plant life. As Coccia describes it in his book Metamorphoses, “we feel so culpable in the fact that our life implies the death of other living things that we prefer to establish an arbitrary limit, an artificial frontier between those beings which suffer (animals) and those which do not (plants).” And yet, as Michael Marder argued in a debate between himself and vegan Gary Francione, “Western philosophers have thought about plants at best as deficient animals, and therefore the violence against animals was magnified manifold when it came to plants.” In other words, because of the Western tradition, we have misunderstood plant life, and as a result, the instrumentalization of plant life has proceeded far apace of that of even other animals. He continues: “If vegans subscribe to this position, they appear still to operate in the spirit of the very philosophical tradition that has devalued animal lives.” This may serve to explain how the logic of veganism, particularly under the capitalism of the early 21st century, has produced such a proliferation of forms of meat-like substance and other vegan foods which often disconnect consumers from the source of their food. It explains many vegans’ assent to the large scale, monoculture agriculture which produces the raw materials for not just omnivores but vegans as well. The being of plants, falling on the wrong side of the dividing line between the things which can and can’t be instrumentalized, Marder suggests, has been more acutely reduced even as the amount of vegans and vegetarians has skyrocketed in the last two decades. As the nature of our global crisis reveals itself to be ecological in new ways, it may be time to reevaluate our relationship not just to other animals on earth, but to the beings which constitute 80% of the biomass of the planet. That is, if our ethical concerns about dwelling and eating, and about the future of the planet, are not just about our own hides, but life on earth as such, then the move to instrumentalize and de-qualify the experience of plants as an inherent part of our moral thought might need to be reconsidered.

Eating Plants

As we agreed with vegans above already, there is no getting around eating plants. It would be literally impossible to live without subjecting some other being to some form of instrumentalization, consumption, and their own form of suffering without ourselves being a plant. As philosopher Simone Weil puts it, “there is only one fault: incapacity to feed upon light, for where capacity to do this has been lost all faults are possible.” We are born, and reborn constantly, by the death of others. And yet, following the laboratory work on plant sensitivity of people like Suzzane Simard and František Baluška, Marder writes that “it is impossible not to feel a sense of wonder, if not shock, upon learning that, after all, to eat a plant is to devour an intelligent, social, complex being.” For Coccia, plants are the “origin of the world,” insofar as they produce all the conditions of life on earth as it were out of nothing, out of the elements themselves: the base of the entire trophic system (nourishment), the atmosphere itself (respiration), and much of the material of the built world (material for dwelling places, medicine, fabric for clothing, etc.). Plants are an image of nourishment itself, the symbol of the fundamental condition of being alive as such. For Aristotle, to be alive meant to be possessed of a nutritive soul, to need nourishment. Plants, for him, posed a self-contained loop, what Bernard Frank would call autotrophy, nourishment accomplished in-and-for-itself. For the Greeks more generally, the word for nature as such (φύσις, physis) is derived from the word for plant (φυτόν, phyton) because the essence of nature is that it is like a plant which grows in wildness toward its own completion and perfection. Unlike other animals, and other people, plants produce the world in which we live, make life possible in every essential way, have never acted as predators or oppressors, and yet we still have to terminate their lives in order to continue our own, even under the most apparently ethical regimens of consumption, such as veganism. If there is no ethical consumption under capitalism, then it is even more fundamentally true that if we follow the trajectory of western thought in the realm of the ethics of eating, then there is no ethical consumption whatsoever.

Marder suggests, instead, that “the question is how to linger in this unsettling condition,” of having to end life, and subject others to suffering, “without ‘getting over’ it, so that ethical sensibilities would be sharpened and enriched, rather than dismissed altogether.” For him and Coccia, the problem with veganism is that it says, categorically – that is, once and for all –, that certain forms of life are acceptable fare (are “fair game”), and others aren’t. What if it is problematic to eat every time we sat down for dinner? What if we had to, as even many meat eaters do, meditate for a bit before every meal on the lives that we have decided have to end in order for us to live our own? If the ethics of eating were not simply about reducing the suffering of animals, but on the conditions of life for the plants we eat as well? At the very least it would lead to a greater focus on farms (which are, after all the actual conditions of life of the plants we eat), on the labor of farmers and the cooks that transform these beings into our meals, a concern not just about the presence of suffering on my plate and its elimination, but the entire system of nourishment which daily constitutes my existence.

Reframing questions of eating around the centrality of plant life is not to, as influential vegan theorist Gary Francione argued in his debate with Marder, derail the struggle for animal liberation, which is still an important and ethically necessary baseline for decisions around food. It rather reframes the logic of the theory itself, and asks us not to focus our understanding of food on a reductive and subtractive approach (we have not even begun to address the relation between veganism and orthorexia), but by positing the inherent value of plant life, and life in general, itself. Not of expanding the scope of moral concern in the sense of eliminating ever expanding circles of forms of life from the dinner table, but in beginning and ending with a concern with nourishment, which can be found in plants. That is, rather than asking whether we should leave animals off the table, considering the ethics of eating plants can suggest that there is no need to even consider putting them there in the first place. It asks us, in other words, to practice attending to the Other, to the radically Other, the one whose suffering we cannot see, the one who needs our ethical consideration but perhaps cannot even ask for it.