Introduction: the Columbian Exchange

At the end of the 15th century, a massive ecological and biological shift began that would change the dietary norms of the planet. For millennia, global food options remained relatively stable, and the evolution of cuisines was primarily facilitated not by the introduction of new ingredients, but by new techniques or recipes. The foods of cultures around the world were guided by the ecological and agricultural limits set by natural and artificial selection. What you ate was determined by where you lived, by the plants and animals that existed in your region. After the first voyages of Columbus, however, this began to change. Slowly, at first, but then much more rapidly, as global trade routes grew up around the colonies that Europeans established in the Americas. At the same time, navigation around the horn of Africa by Henry the Navigator in the previous century also facilitated a greater degree of trade between Europe and Asia. Although trade had existed between these two parts of the world for centuries, the speed of exchange that came with new maritime routes increased this exchange rapidly, allowing for movement of species from East Asia all the way to the East coast of the Americas. Before this point, only Polynesian explorers had connected these two continents, and that was over the course of generations and centuries. By the 17th century, this entire journey could be made in under a year.

These shifts, often called the “Columbian exchange,” were facilitated by the creation of what came to be known as the “Triangular Trade,” a system of North Atlantic shipping routes that shipped raw materials, products, and bodies between the East Coast of North America, Europe, and the West Coast of Africa. The triangular trade emerged in the 16th century, as plantations began growing in the region from the northern coast of South America up through the West Indies as far north as Maryland. As these plantations grew, demand for slaves from Africa increased, and the supply of goods shipped back to Europe grew in tandem. From Europe, weapons and alcohol were shipped to Africa to secure a constant stream of enslaved people, primarily from the Dahomey Kingdom, which grew in power during the period due to their diplomatic relations with Europeans. From Africa to the Americas, slaves; from Africa to Europe, ivory and gold; from the Americas to Europe, cash crops such as tobacco, molasses, rice and indigo, as well as other natural resources like whale oil and timber; from the Americas to Africa, rum and gunpowder; from Europe to Africa, also guns and alcohol; from Europe to North America, luxury goods and textiles.

As ships on these routes of conquest moved across the ocean, thousands of them per century, seeds, plants, and animals were brought along for the ride, some intentionally, some not. From the Americas to Europe, and from there to Asia, came potatoes, peppers, cacao, tobacco, tomatoes, corn, squash of all varieties, peanuts, and pumpkins. Animals included the turkey, guinea pig, and muscovy duck. In the other direction, Europeans brought sugar cane, onions, grapes, coffee, olives, pears, citrus, and wheat. More importantly, in this direction, was the movement of animals from Europe, such as horses, donkeys, pigs, sheep, chickens, goats, cats, large dogs, and honey bees. The movement in each direction deeply affected the modes of life and cuisines of the cultures which received them.

Some of these took a long time to catch on, such as the tomato and potato. For a long time, Europeans were wary of the plants because they are in the nightshade family, and prior to this point, the only nightshades that had existed in Europe were highly toxic. Although potatoes caught on much more quickly, it took nearly two hundred years for tomatoes to gain the trust of Europeans. Originally brought to the continent from Mexico in the 1530s, the plant quickly became popular as an ornamental plant because of its interesting shaped leaves, and richly colored fruits. They were known by many names in various countries, such as the wolf pear, golden apple, and love apple, but not widely eaten. This is because many early aristocrats who tried the “poison apples,” as they came to be called in some parts of the continent, died after eating them. For centuries, they were thought of as dangerous, and were primarily eaten only by peasants, who seemed to be unaffected by them. It turns out the reason the nobles had died after consuming them was because they had been eating off of pewter plates, which are high in lead content. The acidity of the tomatoes had leached the poisonous metals out of the plates, killing them or at the very least making them very ill. Peasants, who did not have the resources to purchase pewter, were unaffected by the plant because their plates were often wood, or some other, less expensive metal like tin. It wasn’t until the end of the 19th century that they began to be trusted among the upper classes. There are notable exceptions, of course. For example, in the Southern part of the United States, they were popular long before this point, with planters like Thomas Jefferson growing a large number of cultivars. We should also note that the cuisine of Italy, unlike that of France, is rooted in domestic, peasant food, rather than the kitchens of the nobility. This explains why the tomato is so central to Italian cuisine today.

Another nightshade, peppers, also began not as a food, but as an ornamental plant when first brought to the far East. Brought by the Portuguese to their trading posts in southeast Asia, the pepper first came from the Americas in the latter part of the 16th century. Also like the tomato, in China, the chili pepper was initially thought of just as a peasant food. The noble gentry of the kingdoms of the region thought of the plant as an unhealthy, coarse food, beautiful but unfit for consumption, for several centuries. In Southern India, which was traditionally poorer than the northern of the country, chili peppers became popular much faster than in the rest of the country because they were a more affordable source of flavor and spice than peppercorns, which had been the primary source of heat and flavor before this point. It took nearly two hundred years after the Portuguese introduction of chilis to the south for them to become integrated into the cuisine of north India. This story repeats itself in most parts of east Asia: the Portuguese import the plant as part of their colonial trading empire, the plant becomes admired for its beauty in the upper class and a food for the lower class, then after several hundred years of its integration into the peasant cuisine of the country, it at last becomes part of the food of the ruling classes. As with the tomato in Italy, the introduction of chilis to the cuisine of Southeast Asia fundamentally changed the nature of food and what we understand to be traditional or authentic diets.

Finally, the last nightshade to change the diets of a country to note here is the potato. Like the chili and the tomato, the potato came to Europe in the late 15th or early 16th century. The first mention of the plant is in a trade receipt from 1567, although it is very possible it came from South America as early as the first few voyages in the 1490s. Like tomatoes and peppers, they were initially looked upon as dangerous because of their inclusion in the nightshade family. And like their nightshade cousins, the potato was initially thought of as peasant food. In South America, Europeans avoided the food not just because of fear of it being poisonous, but also because it was the food of indigenous people, fit only for those who would be subjected to the most arduous work. In the early part of the 16th century, they were first grown in Europe primarily as fodder crops. That is, food to be fed to livestock like cows and pigs. By the middle of the 16th century, however, the potato began to become popular in England, due to its promotion by nobles like Sirs Walter Raleigh, Francis Drake, and Thomas Hariot. Raleigh was said to have introduced it to Ireland during the war of conquest against the Irish that established the first major English plantations there in the 1560s. Because they are relatively easy to grow, and because it is simple to store them during long winters and other times of famine, they quickly became central to the diets of the peasants of northern Europe and Ireland, sometimes to disastrous results, as in the Irish potato famine of the mid 19th century.

The last species I’d like to mention in this section is that of the horse to the indigenous tribes of the Great Plains. While we often think of the tribes of the plains such as the Sioux, Blackfoot, Comanche, Crow, Arapaho, and Kiowa as being nomadic, this was not the case until the introduction of horses by Europeans. Although the first equids evolved in North America before crossing the Bering land bridge, they were hunted to extinction by the people of the continent by 5000 years ago. As a result of the Columbian exchange, horses were reintroduced to North America and created profound change in the cultures of indigenous people. Previous scholarship had believed that this reintegration of horses occurred at the end of the 17th century, after the Pueblo revolt of 1680. But recent research has suggested that it in fact happened much earlier, perhaps as early as the beginning of the 16th century, when Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors traded horses in their first conquests in the Americas. Either way, by the time that European-Americans were pursuing their project of westward expansion and manifest destiny in the 19th century, the tribes above had changed from partially-sedentary foraging and farming cultures into ones entirely built around horses. As we will see, this would have profound effects on the policy of the American government at the end of the 19th century, as colonizers sought to restrict these tribes to reservations.

Creation of the Reservation System

So far, we have seen the ways that European colonization has altered the food landscape of the world in at least two ways. First, as discussed here, it moved species of plants and animals across oceans and continents, following trade patterns, oceanic currents, and other ecological and geographic pathways in permanently changing the species diversity of the earth. The triangular trade, as well as trade routes established primarily by Portuguese colonizers in Southeast Asia, created an exchange of bodies, seeds, and knowledge that allowed for the introduction of ingredients in parts of the world where culture and diet would be forever changed. Second, several weeks ago we talked about the role that colonial plantations have played in creating a division of agricultural labor between different parts of the world. That is, how specialization of monoculture crops in various regions for commercial purposes, efficiency, and productivity in a global market has reduced the biodiversity and capacity for self-support in many parts of the world. In order to maintain productivity in these plantation regions, many staple crops such as wheat, corn, or other grains must be imported from other regions in order to support local populations. This has made many regions dependent on the market, and ultimately those who control the movement of these necessaries of life, in order to be nourished. An extension of this second point is the role that imperial and colonial powers play in cutting off local communities from their traditional sources of food, ways of provisioning themselves, and preparing meals. Nowhere can this be seen more evidently than in the history of reservations for indigenous people during the period of Westward expansion.

Like many of the tribes of the East coast, most tribes of the Western plains had, for millennia, practiced a semi-nomadic system that mixed hunting, foraging, and agriculture in a variety of systems based on the progressive exploitation of natural processes, seasonal cycles, and dynamics of soil fertility. Although no tribe practiced their food culture in the exact same way as the others, each mode of provisioning was generally organized around at least some movement. Many Western tribes built the main part of their seasonal and annual plans for movement around the buffalo, moving with the herds as they shifted from winter to summer grazing regions. Many tribes had a method of converging at certain points in the year with other bands for certain religious, cultural, and ceremonial practices, splitting up for the remainder of the year to pursue their own particular modes of life. In the case of the Blackfeet in the region that would eventually become Glacier national park, this division happened along gendered lines. Men would follow the herds, while women would make their way into the valleys to gather plants and engage in their own practices of hunting, only to return together in the winter. In Montana and Wyoming, certain bands of the Shoshone (the ‘tukudeka’, meaning sheep eaters), took their herds up into the highlands of the Teton Mountain range to graze in the summer, and returned to the valleys in winter, when seasonal pressures became too great. Whatever the particular form of life, these tribes were dependent upon free movement and the continued existence of large populations of animals for their continued existence.

As far back as the end of the revolutionary war, tribes that had sided with England had begun to be moved further west in processes of forced relocation. After the war, England gave America their land grants west of the Appalachian mountains, westward to the Mississippi river. Before this point, growing populations of Euro-Americans had begun to push into this region despite the prohibition by the English crown. But after the treaty of Paris, the practice became not only tolerated, but encouraged by the young American government. Ostensibly, treaties signed between the government and the various Indigenous nations were still in effect, but the terms of these quickly changed as colonizing populations began to occupy the fertile Ohio river valley. After the Louisiana purchase in 1803, this trend continued, and more tribes were pushed–either through explicit government policy or pressures from citizens convinced of the civilizing influence of their weapons–from the Eastern regions of the country into the mid- and far-west. This trend was accelerated with the help of government force when, in 1830, congress passed the “Indian Removal Act”, which provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi". During the presidency of Jackson (1829–1837) and his successor Martin Van Buren (1837–1841) more than 60,000 Native Americans from at least 18 tribes were forced to move west of the Mississippi River where they were allocated new lands. The movement came to be known as the ‘trail of tears,’ and involved people from the Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations. Those that refused to move were killed, making this the clearest example of government directed ethnic cleansing in the history of the United States. The southern tribes were forced mostly into an area known as the Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma). The northern tribes were initially forced into present day Kansas, but movement continued past this point as Kansas began to fill with colonizers. With a few exceptions, the United States east of the Mississippi and south of the Great Lakes was emptied of its Native American population by 1850. The movement westward of indigenous tribes was characterized by a large number of deaths occasioned by the hardships of the journey. It should also be noted that the regions that these people were forced into were not unpopulated, and the sudden appearance of nearly 100,000 new inhabitants put considerable pressure on the region’s already existing cultural and political landscape. Conflicts between relocated tribes and those already living in these areas were constant, and only half-heartedly mediated by U.S. officials.

At the time of the removal, it was claimed that the so-called “Indian Territory” would be a permanent home for the displaced tribes, but this began to change around 1850. After the discovery of gold in California and the Mexican cession at the end of the Mexican-American war, both in 1848, settlers began flooding into the west at rates unheard of before that point. Enough settlers had moved to California in the wake of the goldrush that it was able to register for statehood within two years of the first U.S. settlements. With this sudden rush of colonizers, the government began to reconsider the permanence of the large tracts of lands set aside for displaced indigenous tribes. The first move to further dispossess the tribes living in the west, the government passed the Indian Appropriations Act in 1851. This legislation set aside funds to create reservations in the West to be managed by the U.S. government, ostensibly to protect native Americans from the encroachments of new settlers. Tribes had complained to the government that settlers were beginning to move into Indian Territory, but the government argued that it did not have the funds to enforce the treaties that had been established by the 1830 law. The Appropriations Act set aside that money, but only under certain conditions. Namely, that Native people become restricted to ever smaller areas of land, in increasingly marginal lands where American settlers would likely not have moved either way.

“As Long as There be Game”: Food Colonialism

The other major part of this law that would have profound effects in the decades to come was a newly introduced clause in all treaties which restricted movement of tribes to places where game was available. Many of the conditions that the government had proposed in the new reservations created by the Appropriations act were begrudgingly accepted for lack of better options, but one thing that the tribes could not accept were restrictions on their ability to leave the reservation to hunt during the parts of the year that they had traditionally followed the herds. This was, after all, not only a culturally significant practice which characterized the traditional ways of provisioning the tribe, but for most tribes, it was also their primary source of food, clothing, and other necessities. To restrict them to the reservations was terrible in their minds, but to restrict them from hunting like their ancestors had done before them was intolerable, it was cause for bloodshed and war because it meant death for the tribes. In order to appease these concerns, the government began to write clauses into the treaties that stated that they were allowed to leave the reservations and travel “as long as there be game.” This was enough to settle the concerns of the tribes, but it would have disastrous consequences in the long run.

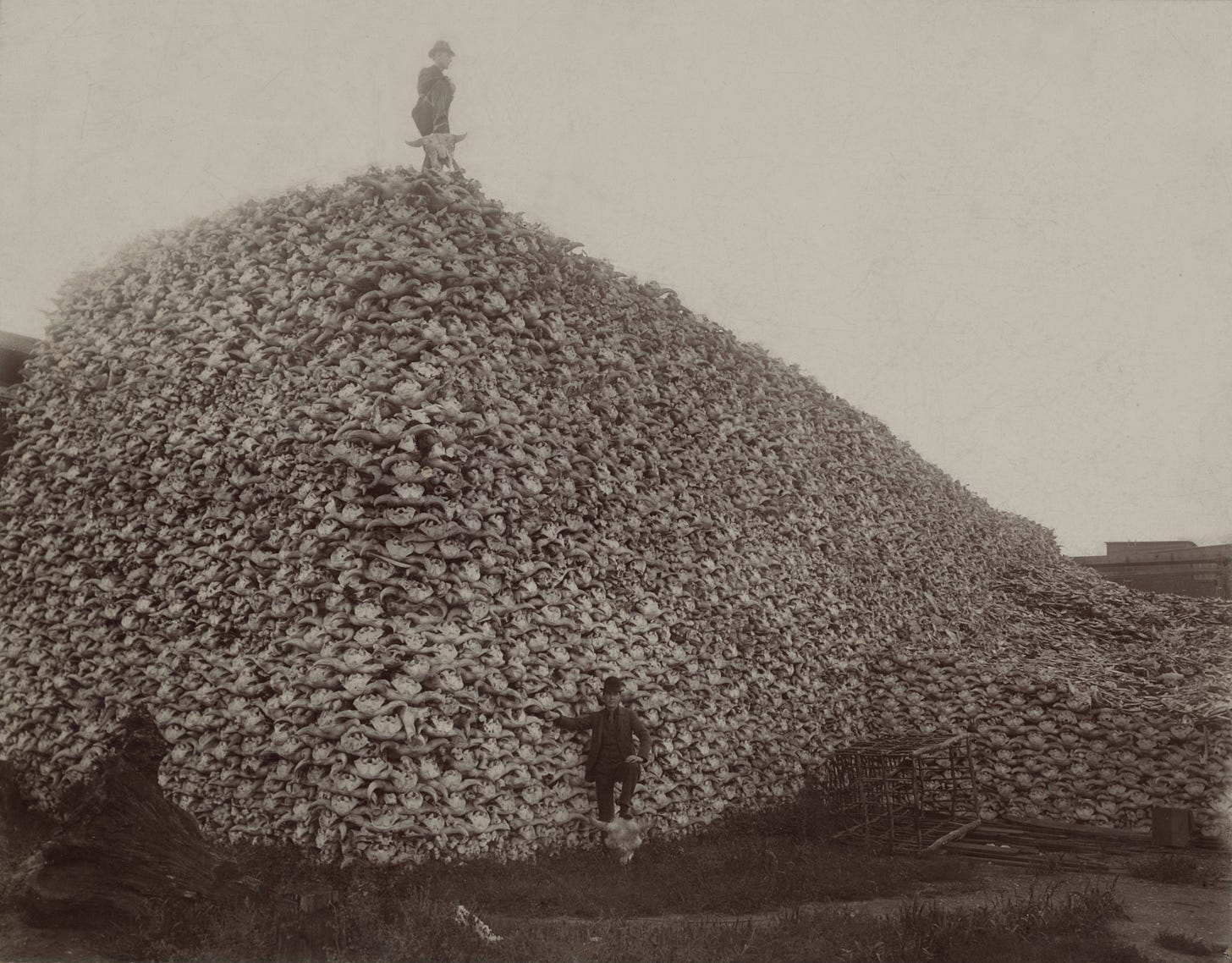

This is because the government, in concert with private citizens and the military, began to systematically eliminate the buffalo in the following decades. Commercial hunting was the primary driver of the buffalo's near extinction. Hunters killed the animals on an industrial scale primarily for their hides, which were in high demand in the eastern U.S. and Europe for use in machinery belts, coats, and other products. The meat was often left to rot on the plains, except for the tongues and humps which were considered delicacies. The construction of railroads across the American West brought a large influx of recreational hunters, who hunted buffalo for sport. Trains would sometimes stop to allow passengers to shoot at buffalo herds from the windows or during short excursions, further decimating the population. The U.S. military actively supported large-scale buffalo hunts as a strategic measure to force Native American tribes onto reservations and to remove their self-sufficiency. Famous military leaders, including General Philip Sheridan, openly encouraged the slaughter of buffalo herds to deny Native Americans their primary food source, hoping to "civilize" them with dependency on government provisions. Human activity also introduced ecological changes that disrupted buffalo habitats. The expansion of agriculture, urban development, and the introduction of cattle on the plains competed with the buffalo for grazing land, reducing their available habitat and food sources. Diseases from domestic cattle, such as bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis, were transmitted to the wild buffalo populations, further diminishing their numbers. These diseases were often deadly to the buffalo, who had no natural immunity against them. By the early 20th century, these factors had combined to reduce the once vast herds, estimated to number between 30 to 60 million in the early 19th century, to just a few hundred by the 1880s.

The elimination of the buffalo had a twofold purpose for the U.S. government. First, tt cleared land to make space for even more agriculture and cattle ranching for the expanding population set on manifest destiny; second, it rendered the treaties made with indigenous tribes effectively null and void. Increasingly, the government, after having restricted tribes to reservations between 1851 and 1890, began to use military force to enforce this restriction since the buffalo were all but extinct. After all, the freedom to move around the west was contingent on the fact that there be game to pursue. The other part of the Indian Appropriations act that was crucial in this story was the money set aside to provision the reservations. It was clear to the government that without buffalo to hunt, and without the right to travel to traditional grounds to gather food and medicinal and spiritual plants, the tribes would be unable to feed themselves. As part of a broader project of assimilating indigenous people into Euro-American culture, the government encouraged tribes to engage in European style intensive farming practices such as row planting and the use of traditionally European crops like wheat. Until the tribes learned how to grow crops like them, the U.S. reasoned, they would have to be provided with enough money to purchase goods from merchants. The Appropriations act distributed cash to the tribes in order to accustom them to getting their food not from the land, but from markets. The reservation system was, in the end, a large scale system for forcing native people from the semi-nomadic forms of life that had been part of their culture since time immemorial into the sedentary, market lifestyle that characterized American laws and culture, centered as it is on the possession of private property, exclusive property rights, and mediated by the dollar.

The most crucial part of this process was cutting off indigenous people from their traditional sources of food as a means of controlling the population. This process of cutting off indigenous people’s access to culturally appropriate foods is known as food colonialism, or food imperialism. This is a process where one nation or culture imposes its food preferences, agricultural practices, and food-related norms onto another culture or country, often overshadowing and marginalizing local culinary traditions and agricultural systems. Such introductions often led to significant shifts in local diets and farming techniques, sometimes improving food security but frequently undermining indigenous food systems and reducing biodiversity. Over time, this type of colonialism can lead to a form of dependency where the colonized region becomes reliant on imported foods instead of local varieties, which can erode traditional knowledge and cuisine. This dynamic still plays out in various forms today, through globalization and the export of Western dietary preferences and food products, impacting local cultures and economies around the world. Cut off a people’s access to food and you can control them much more easily; make them dependent on your systems of food and the control becomes complete.

Other examples of food imperialism include the British introduction of tea cultivation in India. Originally native to China, tea was transplanted to India by the British to break the Chinese monopoly on tea production. This not only altered India's agricultural landscape but also its labor practices and export economy. Similarly, the French colonization of Vietnam brought with it the widespread cultivation of coffee, a crop not native to the region. This move was aimed at turning Vietnam into a coffee exporter for French benefit. The shift had long-lasting effects on Vietnam's landscape and its people, prioritizing export crops over local food security. During the Belgian colonial period in Congo, the forced cultivation of cash crops such as rubber and palm oil led to significant disruptions of local food systems and contributed to widespread famine and suffering among the indigenous populations. In the Pacific, the United States' influence in Hawaii led to the extensive planting of pineapple and sugarcane plantations, which not only transformed the local economy but also the island's ecology and native diets. In Kenya, British colonizers established tea and coffee estates, restricting the Kenyans from cultivating these high-value crops. Such policies not only manipulated local agriculture for British economic gain but also led to a dependency on imported food products among the Kenyan population. In the early 20th century, American fruit companies, notably the United Fruit Company, established vast banana plantations in Central America. These companies exerted significant political and economic influence in countries like Honduras and Guatemala, often at the expense of local farmers and ecosystems, an example famously critiqued as "banana republics." The Soviet Union's imposition of cotton farming in Central Asia serves as an example of agricultural imperialism. This policy turned fertile lands into monocultures of cotton, which led to environmental disasters like the shrinking of the Aral Sea, and displaced local food crops, disrupting traditional diets and agriculture. Finally, we can find current examples of food imperialism in the spread of fast food culture with American brands like McDonald's and KFC in countries around the globe, which has often been criticized for overshadowing local culinary traditions and contributing to rising health issues such as obesity and diabetes.

Food Sovereignty and Food Apartheid

In historical and contemporary contexts, the practical effects of food colonialism and imperialism are the creation of systems of food apartheid. Food apartheid is a term used to describe a severe and systemic form of food inequality where certain areas or communities—often disproportionately populated by low-income residents and minorities—lack affordable and healthy food options. Unlike the term "food desert" which primarily refers to a lack of availability, "food apartheid" emphasizes the intentional, systemic racial and economic inequalities that create disparities in food access. The concept of food apartheid addresses the root causes contributing to these disparities, including racial segregation, socio-economic status, and the uneven distribution of resources. It points to a deliberate structure of separation where choices and quality of life are compromised by one's environment. This framework helps in understanding that food insecurity and poor dietary options are the results of discriminatory policies and practices by public and private sectors that marginalize entire communities. By using "apartheid" in this context, it highlights the deliberate and structured nature of these inequalities, invoking a call to action to dismantle the barriers to equitable food access and to rebuild more just and sustainable food systems.

By imposing food systems on colonized societies and upholding systems of food apartheid, colonizers disrupt what is known as food sovereignty. This is a concept that advocates for the right of people to define their own food systems, emphasizing the importance of community control over agricultural practices, markets, and ecosystems. Originating as a response to the global industrialized food complex, it challenges the prevailing market-oriented approach that often prioritizes profit over health and sustainability. Advocates of food sovereignty argue for the prioritization of local, sustainably produced food sources and the preservation of indigenous agricultural knowledge, thus enabling communities to produce, distribute, and consume food in ways that are environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable. This approach seeks to empower farmers, fishermen, and other food producers to have control over the food production processes, ensuring access to nutritious and culturally appropriate food for all, while respecting the balance of the environment. This movement is spearheaded globally by organizations like La Via Campesina, which see food sovereignty as fundamental to achieving true autonomy and equity in food systems.

In the United States, food apartheid and the elimination of food sovereignty are parts of an ongoing and systematic oppression of indigenous people and other people of color. The process of pushing back against the former and creating the conditions for the latter is known as food justice. Food justice is a movement that seeks to address and rectify the inequalities in the food system that disproportionately affect marginalized communities. It advocates for fair access to nutritious, affordable, and culturally appropriate food for all people, regardless of socioeconomic status, race, or location. The movement highlights the links between environmental justice, sustainable agriculture, and equitable food distribution, pushing for policies that support local farming and reduce barriers to food access. Food justice activists work on multiple fronts—including urban farming, food education, and reforming food policy—to combat the systemic issues that lead to food deserts and the monopolization of food supplies by large corporations. This approach not only emphasizes the right to food as a basic human right but also promotes community empowerment and environmental sustainability as integral aspects of achieving overall food security.

Conclusion

This semester, we have spent several months thinking about our relationship to food. What it is, how we encounter it, how we know it, what makes it good, where it comes from, how we get a hold of it, what kinds we should eat, who makes it, and so on. We have spent significant time not only with the philosophical aspects of food, at the ideas that we have about it, but also with a historical look at the ways that our food systems have been shaped by economic and cultural systems for the last five centuries. Early in the semester, we saw all of the ways that food has been systematically left out of many of the systems of thought in the west, how we overlook it more often than not for matters of convenience and because it is often thought to be something that only lesser classes are meant to have to worry about. Instead of overlooking it, we have tried to stick with the fundamental strangeness of food in order to give ourselves some time to critically consider how important and significant it is to who we are as individuals and as a culture. By reflecting on the various ways that we encounter food, not just through our own taste, but through texts, the stories we tell about it, and media, we have tried to allow for a more genuine appreciation for the various ways it has been both portrayed and overlooked in our lives. By thinking about the value judgments we instinctively use to describe it, we have tried to find new language to make sense of our relationship to it, using new words to express our understanding of it to other people. By thinking critically about the morality of food, using these values to better make sense of how we really experience and interact with food, we have tried to clarify our own relationship with it. The time spent reconceptualizing our understanding of these metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical assumptions about food, we tried to clear the ground for seeing food in the broader economic and political systems which bring it to our table. These final weeks have been perhaps the most important part of this course, as they have been aimed at stepping out of our own particular tastes and desires, and viewing these proclivities in the historical context we are currently living through. We have seen the way that economic, colonial, and imperial systems affect the nature of food itself, how they change what we grow, how we interact with the earth and each other, and how they contribute to dynamics of power grounded in food itself.