In the present, we often think of ourselves as being separated somehow from nature. It’s more or less a precondition for saying that we have an idea of Nature in the first place. That is, an idea of ‘Nature’ as a thing that exists as an independent concept which can be thought in distinction from some other thing: Culture, Civilization, things that are human-derived, etc. Everything from the way our language works, to the way we plan our cities, to the way we build our homes, and even the ways we think about the “preservation of nature”, as if it were a thing to be saved over there, outside the city walls, is reflective of this attitude. Certain words we have for the inhuman world, e.g. ‘wild’ and ‘savage’–which are derived from ‘weld’ and ‘silva’, both words for ‘woods’–suggest that there exists a split between the thing we tend to specify as specifically ‘natural,’ from the rational, cultured civilizations of human existence. Depending on who you ask, this separation is considered a better or worse thing. To some of us it is a blessing. The power that we have to control the environments of our homes and separate ourselves off from the extreme cold or heat of the outside world, the ability we have to get food from a market year round and not have to rely on the cycles of nature for our meals, the capacity to see things after the sun has gone down and spend our nights watching characters on screens until 3 a.m. when the rest of the world is sleeping, etc. All of these things create, as it were, another world inside the shared world of “Nature”, a separated environment over which humanity seems to exert more or less complete control. Then, there are those who believe this separation is disastrous. The way that air conditioning dulls us to the fact that the planet has been warming at an alarming rate; the way that our constant access to food relies on the use of massive amounts of fresh water, petrochemicals, and deforested land; the psychic and spiritual damage that being disconnected from the natural cycles of light throughout the day and throughout the year has caused to us; etc. All of these things, which are of course the same things that the first group praised, rely on what might be seen by this second group as a false world within the wider world of “Nature”, a bubble that will, sooner or later, pop and give us all a rude awakening. And of course, most of us feel both of these attitudes at the same time. What I want to draw our attention to right now is not the difference between the two attitudes, or try to think through which one is right or wrong. But rather simply to point out that both rely to some degree upon the idea that there is a kind of separation between ourselves and the so-called natural world. In the first it is a boon, in the second an illusion.

But where did this idea of separation come from? If, as most people assume, there was a point in time when we once lived, for better or worse, completely within the sphere of nature, then what was the point at which this was no longer the case? When did “human civilization” and “nature” become separate spheres in thought? In this lecture, we will go back to the earliest sources of this conceptual distinction in western language and culture by looking at the various civilizations of the Mediterranean and near East from the Bronze age to Rome.

Anatomically modern humans began to appear in the fossil record sometime between two hundred fifty and three hundred fifty thousand years ago. To give you a sense of scale, that means that for somewhere between twelve thousand five hundred, and seventeen thousand five hundred generations, our species have had the same size brains, body structure, reproductive systems, and other purely physical attributes. That means that if you had a time machine, and plucked your great-great-great-times twelve thousand-great grandmother out of her cradle, before much socialization shaped the way she saw and engaged with the world, and raised her in the present, no one might know the difference. These anatomically modern humans split off from other branches of hominids in the area east of the great rift valley of sub-Saharan Africa and remained almost exclusively in this region for about one hundred thousand years, or nearly half the entire history of our species. In this early ‘paleolithic’ period, humans continued to use rudimentary stone tools, which had been developed by other hominids as early as 3.5 million years ago, primarily for nourishment, i.e. to hunt. These early humans would have also inherited the semi-controlled use of fire from their hominid ancestors who had been using fire since around 1.5 million years ago, or nearly two million years after evidence of the first stone tools. Life during this period likely meant moving along with both the herds of animals that they began to hunt, as well as follow the seasonal shifts in forageable food that grew wild in the region. Such a life would likely not have any strong sense of being in any way ‘separated’ from anything else in the world, neither the climate nor the predators or prey that consumed them and that they in turn consumed.

That is, except insofar as fire was used as a means of processing food into something more nutritious and palatable. Some writers, such as Claude Levi-Strauss, write that the first truly ‘cultural’ tool is the cooking fire, which at night creates at least a semi-permeable zone of distinction between the black darkness of night behind us, and the area where sight, nourishment, and sociality occur before us. This isn’t the closed off walls of a home, to be sure, but it does begin to give off an aura of homeliness, of hospitality, of separation. But then again, scientists also say that without our ancestral hominids’ use of fire to process meat, the nutrients needed to evolve an anatomically modern brain would have been impossible. So, before the human world, in another zone of indistinction between what is cultural and what is natural, the cooking fire and the stone tool are objects that stand at the porous border of the human being as it comes into focus.

A significant megadrought that began around 130,000 years ago drove many of our ancestors out of Africa and into a massive dispersal that brought them into nearly all corners of the world over the next 100,000 years or so. That is, for about half of human history, we were hunters and foragers moving with herds and the fertility of the earth’s plants just in one small area of Africa, then for about another half of the total history of the human being, we were migratory wanderers, slowly inching our way over the surface of the planet, coming into contact with new species of plant and animal, new physical geography, new bodies of water, new climates and weather patterns, new everything. Constant movement was not something unknown to the human being before the megadrought–there had been movement around the small region we dwelled in when in Africa–but this was large-scale movement across continents, every handful of generations coming into contact with what might have seemed an entirely new world. It is from this period that we have record of the first clothing, the first burial practices, the first art. And all of this reflects the changing relationship we had with the natural world. As we moved into a colder climate, we began to wear animal skins, and then to sew clothing together with rudimentary needles. The first burial practices show evidence of an attitude that recognized death as a natural but mysterious thing, something that took the personalities of our loved ones into another place. Art became a record of the thoughts and images within the human mind, which suggests the first steps toward representation of nature. In each of these practices, we begin to see the first stirrings of a world separate from the natural attitude. Natural selection places species in certain regions according to the attributes of their bodies, but clothing became an artificial new skin; many animals grieve, but to begin indicating through burial practices that this is where our loved one is (even if they ‘are not’ with us) indicates the first stirrings of a world beyond or underneath our own; many animals create aesthetically pleasing products, but the representation of nature in images suggests the first stirrings of an internal world that exists in a way different from the one we see before us.

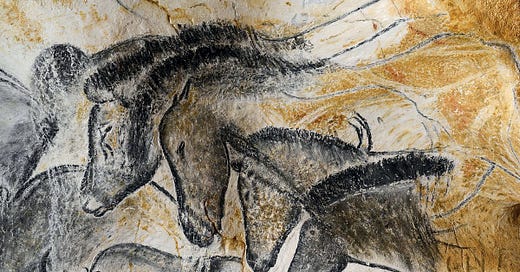

These practices emerged slowly, over tens of thousands of years. The paintings at the Chauvet caves of what is today southern France depict many common game animals of the time, but also new, imaginative creations such as a minotaur and what appears to be a giant vulva with legs. Radiocarbon dating of the paintings indicates that some of the pictures were composed at different times, with as much as 10,000 years separating one part of the painting from the other. That would be like if today, we took part in the completion of an image that had first been painted at the dawn of human agriculture. Shoes began to appear, and star charts mapping the heavens, flutes and sculptures and the first ceramic bowls emerged in different places around the world as inventive humans began to slowly but surely develop the technology that would later allow us to begin creating what we call civilization.

Then, at roughly the same time in both the Levant–that is the fertile crescent around the mediterranean sea–and in another fertile region in what is today central China, agriculture began to emerge about 12,000 years ago. Theories abound as to how agriculture came into being, but the most popular theory hypothesizes that during a particularly warm and stable ecological period just before the Younger Dryas ice age, some humans found themselves for the first time in places where they didn’t have to travel seasonally for food. Rich populations of game animals, nourished on a nearly year-long period of growth for the early grains and fruits that sustained them, allowed for the first permanent settlements for many generations. As favorable ecological conditions persisted, these people began to see that if they put certain parts of their food back into the earth near their homes, that they would grow there as well. Selective reproduction of the biggest and most fruitful wild plants over many generations led slowly but surely to what we today call agriculture. Agriculture allowed this migratory animal that had wandered planet earth for more than two hundred thousand years to being to think of a place as ‘home’. Just as the early fires might have created a rudimentary sense of homeliness around their flames, the earliest settlements, tied to quickly expanding fields of cultivated plants, began to give rise to early evidence of the idea of a ‘homeland’. These places of dwelling separated ‘the world out there’ from ‘the place we live’. The first religious systems and artifacts emerged around this time, largely centered around fertility goddesses which were worshiped as part of rituals that requested continued harvests and which revered the cycles of growth and death through early forms of worship.

It was not until nearly five thousand years after the first evidence of agriculture that large scale civilizations began to emerge. These civilizations were powered primarily by centralized, patriarchal religious systems and armed through the discovery of forging bronze from tin and copper. In modern day Iraq, the Babylonians, Sumerians, and Akkadians developed some of the first systems of law, writing, and large scale architectural projects; in Egypt, the first Pharaohs introduced large scale infrastructure, more complex written symbols called hieroglyphs, and elaborate burial systems and art; on the Greek islands, the Minoan and later Mycanean civilizations developed elaborate maritime trade routes, constructed massive palatial cities, and impressive pottery; further east, in regions we will discuss next week, the Harappan civilization emerged in the Indus River valley; near the end of this period in Canaan, migrants from the city of Ur began to articulate a new, monotheistic religion that would become Judaism; and at around the same late bronze age period, the first large scale Chinese civilizations arose under the Shang dynasty.

Before moving into a discussion of the ideas of nature that emerged in these civilizations, let’s take a moment to reflect on the time-scale we’ve been talking about so far. If we represent the history of anatomically modern humans in a single calendar year, then the period spent just in the area east of the Great Rift Valley would last until about June 6th. The great wandering period of exclusively nomadic existence would last until about December 15th. The very earliest bronze age civilizations would have emerged around December 25th, and the first classical civilizations, such as the Greece of Plato and Aristotle, would emerge around December 29th. Looking forward, the beginning of the colonial period, when capitalism emerged, would occur on December 31st at around 2pm, and the internet would have been born around 11pm, just hours before New Years. This means that at the scale of human history as a whole, the period we have spent in permanent settlements, using technology, living under capitalism, existing online, and so on, is incredibly small. Many scholars argue that it was the agricultural revolution of approximately 10,000 BCE that set us on the trajectory we find ourselves on today. Although there were probably as many ideas of nature as there were groups of people in the paleolithic period, we have almost no indication of what they were, and it is not our place here to speculate on them. But after we began to change from wandering nomads to settled farmers, writing emerged. And through these early records we can begin to see much more clearly how this practice changed our relationship to the rest of the cosmos, and the changes in consciousness which this revolution fostered in the human spirit. In the remainder of this lecture, we will turn to the thought and art of the civilizations living in the wake of the invention of agriculture to see how fundamental it was to our modern conceptions of nature.

The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi and The Descent of Inanna are among the earliest recorded literary texts from the Sumerian people, while The Epic of Gilgamesh is an Akkadian work based on Sumerian legends. Sumer, which emerged around 4500 BCE and flourished until 1900 BCE, was an association of city-states located in the fertile crescent of ancient Mesopotamia. The kingdom was located near the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, which has long been a proposed location for the “two rivers” described in the Hebrew myth of Eden. Its location here meant that the region was particularly fertile, although the annual flooding of the rivers and its floodplain was irregular and unpredictable, causing devastation both when the rivers ran dry and when they violently flooded. To mitigate this threat, the Sumerians built a rich and complex irrigation system of canals, levees, and reservoirs. These massive labor projects were centrally planned and organized by the priest-kings of Sumerian city-states, called Ensi. Their role as both political and religious leaders arose through the idea that to successfully communicate and negotiate with their pantheon of violent nature gods, society ought to be organized around a specialized class that understood their desires and spoke on their people’s behalf. It was this specialized role, in fact, that gave us the idea of ‘hierarchy’, which means ‘rule by priests.’ The agricultural surplus that resulted from these massive, centrally planned labor projects supported the growth of city-states and enabled trade, specialization of labor, and the development of a complex society.

The gods of the polytheistic Sumerian pantheon were anthropomorphic nature deities who controlled various aspects of the natural world. In their various myths, the world of nature was created through the sexual union of a variety of gods, depending on which myth we focus on. As such, sexuality and reproduction plays a central role in many of their myths. Inanna, who shows up in more Sumerian myths than any other deity, was the goddess of love, sexuality, reproduction, and war. She was the force that brought things together, coupled them, produced more, and then presided over their death. In other words, she was closely associated with some of the most fundamental forces of nature, those parts that had to do with life and death. Like Inanna, Dumuzid was associated with a wide range of seemingly different forces, presiding over things like reproduction and milk, and was often listed as one of the human priest-kings of Sumer. In The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzid, we see the importance of these Ensi priest-kings for the continued fertility of the land in the Sumerian mind. Inanna, who represents the natural world, is wed and couples with Dumuzi, a man who provides her with the milk which allows her to do her work of reproduction. In the myth, the priest-king puts seeds into the earth, responds to Inanna’s desire, and this pleases her so much that she yields all the fruits of the harvest. In this way, we can see in this myth the Sumerian conception of nature as unpredictable and violent, and the idea that in order to deal appropriately with the gods, a centralized, hierarchical state ruled by priest-kings is necessary.

In the Descent of Inanna, the goddess descends into the Kur, an underground cavern where the dead go after life. Various versions of the myth exist, but most agree that she descends in order to learn more about the powers of the dead. She spends three days in the underworld, which is the most that anyone can spend there without actually being dead, so after that point, it is assumed in the overworld that she is lost forever. Several of the other gods, deciding that without Inanna’s powers, the world cannot go on, retrieve her, and when she returns, she finds that her husband Dumuzi has not been properly mourning her. As a result, she punishes him by sending him to the underworld instead. Eventually, she decides that instead they should periodically switch places, with each spending half of the year in the underworld. This, for the Sumerians, explained the cyclical changing of the seasons, with her time in the land of the dead representing cold, lifeless winter months when she is gone from the world, and fertile, lush seasons when she is present in the world.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, we are introduced to another priest-king of the region, based on a legendary king of Ur. Gilgamesh is centered around the relationship between the king and a man from the wild named Enkidu. Enkidu was created by the gods to keep Gilgamesh from oppressing his people. When they first meet, they have an epic battle that represents the struggle of man against nature, or better, man trying to overcome his natural state. There is no clear victor in the battle, but it leads to a friendship that develops between the two men. Enkidu eventually becomes civilized when he is subdued and seduced by Shamhat, a sacred priestess of the temple of Ishtar, another name for Inanna. As in The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi, it is the relationship with the gods that comes through the temple which allows for us to conquer and control nature. In this case, human nature, or what humans are outside of civilization.

While the Sumerian gods of nature are forces that can be negotiated with, coupled with, and to some degree conquered, the god of the early Canaanites was one that instead stood outside and above nature altogether. The relationship that the Canaanites had with their god was not one of mixture, contact, or sexuality, but a covenant made in which the people agreed to keep their god’s laws in exchange for his guardianship. In this mythological tradition, a man from Ur named Abraham was commanded by El or Yahweh to travel out of Sumer to the west to settle in a new land near the shores of the Mediterranean. In their creation myth, recounted in the book of Genesis, the world was created not through the sexual union of various gods of nature as in Sumerian mythology, but rather through the word of God. It is a divine conception, a plan, that gives rise to the various forces of nature, which are not themselves deific, but only follow the word of the creator god. As in the historical Levant of the Natufian culture mentioned before, in the garden that Yahweh creates, food is plentiful and provides for the two humans who live there without labor. Then, the woman disobeys God by eating from the tree that gives knowledge of life and death, and compels the man to eat it as well. They become conscious of their bodies, of their nakedness, and are ashamed of breaking the law set forth in the word of God. For this, God casts them out of the garden of Eden. One of the first things that God tells them when they leave is that “cursed is the ground because of you;/ in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life;/ thorns and thistles it shall bring forth to you;/ and you shall eat the plants of the field./ In the sweat of your face/ you shall eat bread/ till you return to the ground/ for out of it you were taken;/ you are dust and to dust you shall return.” In other words, while in the garden they could eat freely, because they broke the law, their punishment is agriculture. One of their sons becomes a shepherd, and the other a farmer.

Three key elements should be taken out of this account. First is the importance of the word in the creation myth of the early Jewish and then later Christian accounts based on this story. It is through what the Greeks would later translate as logos, meaning word or reason, that the world of nature is organized the way it is. The word of God is the ultimate account of the reality of the world, not the passions and sexual frustration of fertility deities. The word of God is also what ultimately determines how we should act in the world, for no other reason than that is what God said. Notice also that the relationship that exists between this God and his people does not involve trying to appease him with actions that will bring fertility, but rather is based on a covenant, a verbal agreement. There are many sacrifices in the Canaanite religion, but these occur not because they represent activities that we perceive in the natural world, as in Sumer, but rather because that’s what God says to do. There’s no other reason. Later, early Christians will find in the work of Plato and Aristotle a philosophical account of this principle. For them, we can understand the world only through an explanation, through logos.

Secondly, in a related vein, while the Sumerian gods–and many of the gods in other ancient Mediterranean religions–are present in nature, as natural forces, the God of the Canaanites exists outside and above nature. Sumerian and other polytheistic gods are ones that we can come into contact with. We can find them on the tops of mountains, in the waters of the waves, at springs in the woods, and in our own bedrooms. They are gods that, though elusive and often only contactable through elaborate ritual, can be perceived by the senses. Yahweh, on the other hand, only ever appears through messengers, or very seldomly as a voice. The messengers bring word from God of what we are supposed to do, or a voice speaks to us when we’re in the desert. What this means is that while the polytheistic nature gods of other Mediterranean religions are immanent, the god of the Canaanites is transcendent. He exists before, after, above, and outside of nature. In the same way that we tend to believe that we own the things we make because we pre-exist them and give them form, God, as the maker of heaven and earth, is the lord of nature as its creator. Whereas in other religions, we contact the divine through nature, for the Canaanites, the nature of matter is just a created thing, and everything divine or pertaining to the spirit exists in another realm, including our own souls when we are not trapped in our meat bag of a body.

The final element to notice here is that for the Sumerians, agriculture is part of the labor that brings us closer to the gods, while for the Canaanites, it is a punishment. For the Sumerians, farming is a way to interact with natural forces, to partly bring them under our control, and the rituals of religion are designed to ensure the ongoing cooperation of the gods. For the Canaanites, humans farm because they disobeyed the word of God. The speech that Yahweh makes when he casts Adam and Eve out of Eden outlines three consequences of disobedience: there will be blood and violence, birth will hurt, and we’ll have to farm if we want to eat. In the renaissance accounts of nature that we will read later in the semester, this idea will become crucial. For the Puritans colonizing North America, agriculture and the efficient use of land will be understood as the penance that we have to pay for human sin. And anyone who doesn’t make efficient use of land, doesn’t toil to feed themselves, will be seen by them as ungodly.

In Greece, the bronze age was the time of heroes and gods. Ancient Minoan and Mycanean cultures were, like those of Sumeria, civilizations organized around the grand palaces of kings. Because the shores of Greece are hot and rocky, only a few areas were agriculturally fertile, and the ancient Achaeans relied more heavily on maritime trade and small farming villages than large, complex irrigation, and so while they were centralized and hierarchical, they were generally smaller and more dispersed than in Sumer, Babylonia, and Egypt. Prior to the rise of the Minoan culture, fertility cults in the Aegean basin were widespread, worshiping many of the same gods as the other religions of the region, although they went by different names. The Ionian invasion, when peoples out of the north conquered the area and gave rise to the Minoan and the Mycanean civilizations, brought new gods like Poseidon and Zeus, supplanting a largely matriarchal religion with one centered around patriarchs.

Like all Bronze age civilizations in the Mediterranean basin, the Mycanean culture abruptly collapsed in around 1200 BCE. No one is exactly sure why this happened, but a combination of natural disasters, economic collapse that spread throughout the highly interdependent civilizations of the late Bronze age, and the arrival of the “sea people”–a name for an as yet unidentified civilization that raided around the Mediterranean basin recorded by all the major civilizations of the time–have been put forth as explanations. In the mythological accounts, the heroic age ended with the famous Trojan war, in which the last generation of great heroes was slaughtered on the beaches of modern day Turkey, or met their tragic downfall on their return home. After the collapse of the palatial civilizations, Greece entered a ‘dark age’ that lasted until roughly 800-700 BCE. While the Linear B system of writing existed during the Mycanean era, writing was completely lost and Greek culture was one that was passed on orally for approximately 500 years. During this time, stories of the heroic age and its associated gods were transmitted orally by traveling bards. In around 700, these stories began to be written down as life began to become organized once again around city-states called poleis that experimented with a new form of government called democracy, or rule by the people.

Two of the most famous poets who collected these stories are referred to as Homer and Hesiod. It is unclear whether they were really individuals, or whether they were groups of people who collated these myths, but either way, these two poets are credited with the writing of four books that became the foundational texts of classical Greek culture: Hesiod’s Theogony and his Works and Days, and Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Several hymns were also ascribed to Homer, from which I have shared some readings, but the authorship of these is even more doubtful. In these texts and the ones derived from them, there is no independent category of “Nature” which stands over and against human culture. Even more than in the Sumerian mythos, Greek conceptions of the world are ones where the divine, the human, and the natural all intertwine in an elaborate warp and weft. Love, rage, revenge, wisdom, and other forces of the heart and mind are conceived as gods that exist in the same breath as those of rivers, fire, storms, and earthquakes. The gods of the Greek pantheon are often anthropomorphic, but the way they are portrayed is as if the divine, the natural, and the human all exist at once within a single action or thing. For the early Greeks, nature was hardly an object, but rather a force that worked against or in support of human history in the same way that wind could be said to work against or in support of the lives of trees, or water against or in support of stone. As the German poet Schiller wrote centuries later, “The Greeks felt naturally, while we feel the natural.”

Hesiod’s Theogony tells about the origins of the world and the births of the gods. According to him, the world of nature began as chaos, meaning ‘emptiness,’ ‘vastness,’ or ‘void.’ Unlike in the Sumerian mythos and that of the Canaanites, there is no act that brings nature into being, only spontaneous generation. Until Plato and Aristotle, there is no sense in Greek mythology that anything or anyone set the universe in order, it simply came to be. It is from this that we get the Greek word for nature, physis. This word is derived from the verb phynesthai, or ‘to grow,’ ‘to bring forth’, ‘to become,’ which is itself probably derived from the word phos, meaning “to appear”. This set of words is also related to the word phyto, meaning ‘plant,’ which is a thing that comes into being as if from out of nothing, flowering forth and becoming what it is from within itself. Nature, for the Greeks, is itself the generation of the gods, it is the principle that makes all things human, divine, and otherwise. The Earth, in Hesiod’s telling, is the first thing that spontaneously arose out of chaos, followed by Tartarus, the place where the dead go, and Love, the force that both joins things together to reproduce and also “demolishes wise counsel and reason in the hearts of gods and mortals.” The rest of the poem describes the first ages of the world, beginning with these primordial forces, then acceding to the more individualized, Titanic forces of Kronos and Gaia, and then from there to the familiar generation of Olympian gods we are familiar with.

In Works and Days, Hesiod describes the lives of humans and the nature of our work. As in the Canaanite mythos, agriculture is thought of as a pain. While the climate of the Mediterranean made farming easy in one sense, the rocky terrain of many of its regions made it nearly impossible in others. Unlike the Canaanites, however, agriculture is not difficult because it is a punishment for human sin, but rather because that is the way of the world. Since the world is not a planned, created thing, but rather something that is spontaneously generated, the difficulties of farming and of interacting with nature in general are a consequence of the nature of nature itself. This is something to be lamented, to the Greeks, but only insofar as the world is itself painful and tragic. There is something intrinsically difficult about human life, and farming is held up as a symbol of our relationship with nature because it is hardship that characterizes what it is like to be a living thing. We’re born, we suffer, we die, that’s it. And the gods are not to be blamed or feared because of this, but rather held in awe the same way that we hold the grandeur of nature in awe.

In the selections from the Homeric Hymns, the poet tells the story of Demeter, Dionysos, and Pan, three nature gods. Demeter’s story is similar to that of Inanna from the Sumerian mythos. Demeter, whose name is derived from the words for Earth (De, or Ge) and Mother (meter, mater), was the goddess most closely associated with fertility and the fields, but did not have the same associations as Inanna with sexuality and war. In the story, Demeter’s daughter, Persephone, goddess of spring, growth, and plants, is taken by death–in Homer’s version, this plays out as an abduction by the god of the Underworld, Hades. Demeter is furious that her daughter, an immortal goddess, could be taken from the land of the living, and travels across Greece to find her. In parts of the poem not included in the selection, she visits the home of king Celeus of Eleusis, and in her sorrows works as a wetnurse to their son, Triptolemus. Then, after not finding her daughter, she goes to Zeus and demands that he make Hades return Persephone. Before Persephone leaves the underworld, she eats several seeds of the Pomegranate fruit. This means that for several months out of the year, she has to return to the underworld to continue being Hades’ queen. In this way, the Greeks explained the changing of the seasons in a way similar to that of the Inanna myth.

This myth is also the story that sits at the center of the cult of Eleusis, which was the longest running public rite in Greek society. In it, participants walked 12 miles from Athens to Eleusis, given a psychoactive substance, shut in a dark room, the story was told, and as the substance started to take effect, a bright light at the center of the room projected cut out images of the myth onto sheets floating and rippling above the participants, and then they were shown a sheath of grain. If this sounds familiar from Plato’s allegory of the cave, that’s intentional. This public rite, which was undergone by every Greek man and woman, was central to Greek conceptions of nature. By all accounts, it was an extremely moving experience, and shaped the way that they understood the cycles of nature in profound ways. Socrates and Plato, on the other hand, thought it was a farce, and that the only way to truly understand nature was through the process of reason described last week.

Last week, I described the work of the pre-Socratics, as well as Plato and Aristotle, who came after Homer and Hesiod, so I won’t discuss them again this week. But the last Greek I would like to briefly mention is Xenophon, another student of Socrates. Xenophon, like Plato, wrote Socratic dialogues based on their teacher’s ideas. In his Oeconomicus, Xenophon discusses the art of agriculture and describes it as the finest and most important knowledge that a person can have. The word economic comes from the Greek words oikos (home) and nomos (rule, law, or norm). Together they refer to the science and art of governing the household farm, which was the engine of Greek society. Knowing how to manage fields, keep storehouses in working order, grow crops, harvest and process grains, and cultivate fruits such as olives and grapes, was essential knowledge in Greek society. With this knowledge, the Greeks were able to live within the natural cycles of the harsh mediterranean landscape. For Socrates and his interlocutor Isomachus, this knowledge is gained through observation, experimentation, and reason. Compare this, then, to the agricultural practices of Sumer in The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi. There, it was a centralized, hierarchical bureaucracy that mediated the relationship between humans and nature; here, it is the shared knowledge of the Athenian citizenry that allows for negotiation between the natural world and the human being.

Finally, after the decline of classical Greek society in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquests, the region entered what is called the Hellenistic period. During this period, Greek thought and culture was spread throughout the empire, and influences could be found from Italy to the Indus Valley. In this period, Roman civilization came to dominate the region politically, economically, and martially. While many of the Roman nature deities were transposed from those of the Greeks, Sumerians, Egyptians, and other Mediterranean civilizations, there were distinct differences that we can see most prominently in the agricultural texts of the time. For Cato the Elder, Marcus Varro, and Lucius Columella, agriculture was the paragon of civic virtue, the highest good in Roman culture. In these three poems all entitled De Re Rustica or De Agricultura, as well as the more famous Georgics of Virgil, Roman authors distinguish themselves from their Greek counterparts through their insistence on practicality. While Xenophon includes some practical knowledge in his Socratic dialogue, he is primarily concerned with the principles of farming and the role that it plays in the cultivation of personal virtue. For the Romans, farming is valued because of the role it plays in the maintenance of the state, of civil society, and of public virtue. For the Romans, farming is, unlike in Sumeria and Greece, not primarily a way of living more harmoniously with nature, but a practical method of contributing to the perpetuation of human (and specifically Roman) civilization. This is indicative more broadly of the way that Roman conceptions of nature are subservient to their conception of the greatness of culture. The god Poseidon, who was primarily a sea and earth god to the Greeks, became Neptune, who was more closely associated with horsemanship and military power. And Zeus became Jupiter, whose primary role was the maintenance of the laws and the state. While the classical Greeks began to introduce a distinction between physis and nomos, or nature and human laws and customs, it was not until the Romans that a sharp distinction between nature and culture was fully articulated. This understanding of agriculture, and the associated subordination of nature to culture, in both Xenophon and the Romans, will come back in a powerful way when we get to the ideas of the American revolution.

So, to go back to the beginning of the lecture, where did the division that today we take for granted in the West between human life and the world of nature emerge? Was it at already present in the pre-human creation of tools? The first stone age fires? The invention of the imaginary world in the first cave paintings? The birth of agriculture and the idea of a country in the Levant? The institution of organized, hierarchical religion in Mesopotamia? The discovery of a transcendent god in Canaan? The rise of reason in the Greek world? Or the precedence of civic virtue in Rome? It is probably not any of these exclusively, but rather occurred through a long, gradual process that continues to the present. And then again, we can look at it the other way as well. Perhaps the interdependence of human life and nature persists through all of this change, and still exists in the present. As we continue this semester, we will continue to see many ways in which these ancient and classical ideas of nature in the West are preserved in the ideas and practices of the present.